Today on Pitchfork, we are celebrating the messy, game-changing, era-defining genius of the Wu-Tang Clan with five new reviews: two albums, two solo projects, and a film score.

Of the many monikers, aliases, and riffs that whizz like flying guillotines across Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), only one gets spelled out: Method Man. The Staten Island rapper’s self-titled song, a geyser of idioms and allusions to cartoons, commercials, and weed, offers the earliest proof that Wu-Tang is for the children. His puerile free associations spring off and glom on to RZA’s dusty drums and piano plinks like chewing gum on teeth. “You don’t know me and you don’t know my style,” Method Man taunts, an ethos that would come to define his debut album.

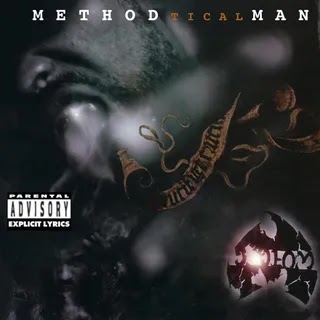

Released a little over a year after Enter the Wu-Tang in the fall of 1994, Tical opened the fusillade of solo Wu-Tang albums that followed the clan’s rowdy debut. It was supposed to be second in line, but Ol’ Dirty Bastard blew his $45,000 advance from Elektra on a hooptie and had an erratic recording schedule. Meth stepped up with a debut informed by drug-altered states and the grim environments that make them desirable. It lives in the shadow of the canonized Wu solo albums that succeeded it, and relative to the cold precision of Liquid Swords, the wry unpredictability of Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version, and the dizzyingly stylish pulp of Only Built 4 Cuban Linx, it’s not as refined, eclectic, or cinematic. But that’s by design.

Though he became the breakout star of the group, thanks in part to his frequent collaborations with non-Wu artists like Biggie and Spice 1, Tical is an interior record. Across these reclusive tracks, Method Man’s primary concerns are securing refuge and dispatching threats. Named after methtical—Staten Island slang for weed—but also deeply shaped by angel dust, Tical molds the suave playfulness of “Method Man” into anxious evasion. The music is claustrophobic and quicksilver, Method Man’s liquid delivery sliding around, across, and into RZA’s jigsaw beats. “Bring the Pain” is a flow clinic in which Method Man skillfully drifts in and out of meter over a purring sample of Jerry Butler’s soul gem “I’m Your Mechanical Man.” Though he sounds unbothered as he peels off boasts and references to Star Wars, Driving Miss Daisy, and Kris Kross, his fleet-footed rhymes are charged with unease. “Is it real, son, is it really real, son?/Let me know it’s real son, if it’s really real,” he rattles off on the jittery hook.

In a 1994 ego trip profile, Method Man said the goal of the album was to “take niggas outta hell for a minute,” but the music never feels escapist in the traditional sense. He presents escape as active and adrenal, his thoughts racing as he chases relief in a rhyme or an inhale. Music about getting high often basks in the way weed dilates consciousness and stretches time, but Tical is more like a cigarette break on the clock, every puff underscoring the brevity of the comfort.

Most of the verses are functionally strings of battle raps, harking back to both the Staten Island cyphers where the Wu members cut their teeth and the internal competitions that would determine who ended up on the Clan’s songs. “Meth vs. Chef” epitomizes that mode, staging a friendly skirmish between Method Man and Raekwon. But Method Man’s shit-talking often doubles as venting. On single “Release Yo’ Delf,” he sounds outright annoyed. “Notice, that other niggas rap styles is bogus/Doo doo, compared to this versatile voodoo/Blazing, the stuff that ignites stimulation inside ya/’Cause I be that hell sure provider,” he raps, slyly emphasizing the first counts of each measure. He has a singular gift for stylizing transitions between words and bars, a skill that makes his rapping conversational and personable even when he’s taking heads.

The opening lines of “Sub Crazy” are full of artful pauses and change-ups that string threats into a vignette: “What up, opp? Niggas is strapped, ready for war/On the ill block, things just ain’t peace no more/Fuck it, if you ain’t with me then forget me/Niggas tried to stick me/Retaliation, no hesitation, shifty/Creepin’ niggas in the dark, triggers with no heart/Ripping ass apart, I be swimming with the sharks now.” The rhymes are polysyllabic but unembellished, his voice instead stressing the shifts in cadence that stitch all the images together. Method Man would later become revered for his smooth and assured voice—a pillar of orthodoxy in the midst of the Wu ruckus, and the legible counterpoint to Redman’s freehand word splatters—but here he’s as dynamic as he is suave.

RZA’s inkblot beats are just as fluid; the sooty drum kits, corroded piano melodies, and spectral voice samples shroud the album in moody darkness. On “Mr. Sandman” he degrades the Chordettes’ cheery ’50s pop standard of the same name into an eerie death wail and sprinkles it over a dulled breakbeat. He tops the cavernous bass of “Sub Crazy” with a chilly, melodic howl and the disturbing sound of a bomb falling. “Release Yo’ Delf” flips Gloria Gaynor’s anthemic “I Will Survive” into a dubby marching drill. “Keep it moving, baby, we be moving,” chants Method Man, the drum major to RZA’s one-man band.

Compared to Enter the Wu-Tang, Tical’s production has briefer skits and fewer identifiable movie and soul samples; that may be the result of a flood that laid waste to scores of completed tracks and beats in RZA’s basement. Method Man ended up having to re-record verses over refurbished beats, a snag he has credited with diminishing the album’s quality and impact. But RZA’s jagged and phantasmic productions fit Method Man’s restless rapping, underscoring the recurring mentions of death, loss, and disease. “I’m from a small town where nigga do or nigga die,” Method Man wheezes on “Stimulation,” distilling the bleak world of Tical to its solitary core.

Tical is essentially a photographic negative of Enter the Wu-Tang; the Shaolin mythology and bonds of brotherhood dissolve as Method Man pushes through the abyss alone, comforted by fleeting pleasures and his loved ones. “All I Need” provides the album's sole moment of respite, Method Man promising his girl better days while thanking her for back rubs and support. RZA’s surgical sample of Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell’s “You’re All I Need to Get By” leans into the longing of Method Man’s writing, pulling and compressing the source’s melody without the vocals. The platinum-selling remix with Mary J. Blige would become the canonical version of the song (and cement Method Man’s begrudging role as Wu-Tang’s resident heartthrob), but the original captures the indelible blues of the track. Method Man speaks to and about his muse, who would later become his wife, as if trying to condense the expanse of his love into a single message.

Tical’s singles ended up having a longer tail than the record as a whole. Chris Rock named a comedy special after “Bring the Pain,” and 2Pac, Missy Elliott, and R.A.P. Ferreira, among many others, interpolated it. The “All I Need” remix became a Top 10 hit and a hip-hop soul classic. But the full album isn’t as lauded as 1994 rap albums like Nas’ Illmatic, Notorious B.I.G.’s Ready to Die, Scarface’s The Diary, and Redman’s Dare Iz a Darkside—a legacy in many ways attributable to the caginess of its elusive narrator. No single song or sequence quite conveys who Method Man is; the constant shapeshifting reveals his style and interests but not his worldview or background.

In its narcotic detachment, though, Tical anticipates the groggy inward turns that rappers as varied as Lil Wayne, Kid Cudi, Earl Sweatshirt, and Lil Peep would take as drugged states became a sonic and narrative pillar of hip-hop. Method Man dusted so Future could sip. There’s a distinctive openness to Tical compared to its distant cousins, however. Unlike the many stoner anthems (some of them coauthored by Method Man) and laments that succeeded it, Tical declines to foreground its muses; the benders that shape it are always subtext, never a focal or talking point. That chronic distance allows the pleasures and miseries of addiction to go unfixed, instead of cohering into an easy takeaway about the drugs or the user.

Method Man baked that slipperiness into the record when he scrapped the album’s weed-referencing original title, The Burning Book, in favor of hyperlocal slang that couldn’t be reduced to a lifestyle or brand. Tical, he explained to High Times in 1995 when asked what it meant, was a “word that’s gonna mean more shit in the future”—a deflection and a bit of prophecy. In 2017 Method Man told Desus & Mero that “tical” stood for “taking into consideration all lives.” Though that clearly retroactive riff adds no new dimensions to the record, it feels congruent with RZA and Method Man’s expressionist songwriting. In their view, slang—like samples, like flows—is meant to keep morphing, keep moving. Sometimes a stride is as striking as a story.

0 comments:

Post a Comment