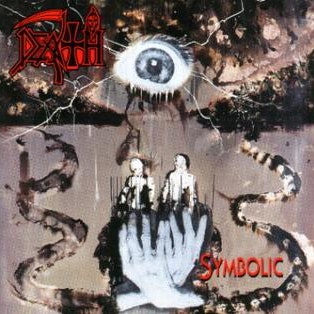

Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit the 1995 album by the incalculably influential Florida death metal band, the most melodic and refined album of their career.

Like the horror section at the local video store, or the spot outside the mall where kids would cut class to smoke cigarettes, the music recorded by Chuck Schuldiner with Death between 1987 and 1998 exists as a safe haven. For those drawn to these seven studio albums by the pioneering death metal band, the music became a fortress to guard against the mainstream, a place where a lot of outcasts gathered to find their identity.

Because no two records featured the same lineup, and because each one built so steadily on the sound of the last, every era in Schuldiner’s brief career attracts its own set of devotees. There are those who stand by the early material, like 1987’s Scream Bloody Gore, with its weed- and beer-scented basement atmosphere. These were the songs Schuldiner wrote at his mother’s house in Florida after hearing the UK extreme metal band Venom and feeling “scared, blown away, amazed”—in that order. The music is bludgeoning and immediate. And the lyrics, from the moment they escaped his teenage mind, inspired death metal bands for eternity to summarize zombie attacks and the plots of slasher flicks in the goriest ways imaginable.

Others came on board with mid-era material like 1991’s Human, which traded violent thrills and thrashy riffs for more sophisticated interests. In these songs, Schuldiner, then in his mid-20s, took his first stabs at imagining what adulthood might look like beyond your general torture and zombie apocalypse. His lyrics explored more existential horrors, the everyday evil of emotional betrayal and misuse of power; he began playing with musicians like Cynic’s Sean Reinert and Paul Masvidal who took inspiration from jazz and progressive rock, accompanying the songs with spacier textures, in dazzling time signatures.

As the provocative, blunt-force metal that Death helped popularize in the ’80s was gaining an audience outside its loyal scene—with heavy bands signing to bigger labels, getting rotation on MTV, and, in the case of Cannibal Corpse, appearing in a blockbuster comedy—Schuldiner quickly lost interest. He was sensitive and soft-spoken, with a slight lisp and gentle Southern drawl, but he was also intense, impulsive, and unafraid to speak his mind—the kind of person you’d want on your side in an argument. He cycled through bandmates and bailed on tours, rallied against the media and burned bridges. Occasionally, his rebellion was more lighthearted. When he appeared at MTV’s Headbangers Ball in 1993 alongside peers donned in tees with pentagrams and illegible logos, he can be seen wearing a shirt with no text, just a few adorable kittens.

At the time of its release in 1995, it would have been difficult to predict the enduring, unifying appeal of Symbolic. To some fans, this melodic turn was a disappointment—neither as brutal as the early material nor as outwardly progressive as the recent stuff. To the world at large, it came and went, dwarfed by post-grunge and the oncoming wave of nu-metal, overshadowed by bigger sellers on Death’s new label, Roadrunner, like Machine Head and Sepultura. (Roadrunner attempted to promote the album alongside their other death metal releases in a blanket advertisement, which resulted in an angry phone call from Schuldiner, doing everything possible to avoid blending in with the scene.)

Schuldiner might have seemed confident, but he too struggled with what exactly this catchy, complicated music was supposed to be. Despite the tight structure and memorable refrain of a song like “Crystal Mountain,” the sound was too hard-edged to feel like straight rock music; and despite the dissonant riffs and vivid aggression of a song like “Misanthrope,” the band never stays in one place long enough to let you find the groove.

At this time, Schuldiner was growing frustrated with his singing voice—the element that bound together the disparate phases of his career and connects Symbolic most directly to other death metal bands at the time. Less guttural than what death metal vocals would become and more abrasive than the thrash metal that inspired him, Schuldiner’s instinctive voice is an inimitable texture against his music, with a whipping momentum, like fire tearing through piles of leaves. “I don’t know that he ever consciously thought to sing that way,” his mother, Jane Schuldiner, recalled of those early rehearsals in her basement after her son had dropped out of high school to pursue his dream of playing guitar in a metal band. “It just came naturally when he started singing and playing that kind of music.”

Schuldiner’s career is defined by the relationship between his ever-increasing skill as a musician and his unwavering vision. By Symbolic, he had become one of metal’s finest guitarists—someone whose playing summons a singular response, a feeling you can only get from hearing his records. So many of his riffs, like the one that arrives 45 seconds into the opening title track of Symbolic, seem to hurl themselves against the speakers, like someone backing up and repeatedly trying to kick down a door. He sought the same attack with his voice, and he often felt disappointed. “All the music is done,” he would announce to his bandmates, “now I have to ruin it with my vocals.”

Schuldiner spoke often about enlisting an actual singer for the band. His dream was Ronnie James Dio, whose operatic tenor helped elevate Black Sabbath and Dio classics into nightmarish hymnals. Schuldiner, in comparison, seemed to bark the lyrics, relying on repetition, echoing effects, and dramatic flourishes to mirror the growing dynamics of his writing. On Symbolic, he sometimes sounds more like the singer of a hardcore band, shouting through gritted teeth so you can register every word from deep within the thrashing crowd: “I don’t mean to dwell,” he screams in the opening lines, “but I can’t help myself.”

With Schuldiner’s vocals sanded down to skeletal bursts, the music on Symbolic was newly sprawling and surprising. He incorporates classical guitar into the ghostly outros of “Crystal Mountain” and “Perennial Quest,” giving the sense of a quiet, vulnerable landscape on the outer edges of these epics. Passing melodies from “Sacred Serenity” and “1,000 Eyes” have a sentimental pull like the score from an action film set in space. Without the clear verse-chorus structure of more traditional heavy music, even the most palatable death metal songs can feel like an amorphous revolving door of riffs: Schuldiner always took pleasure in finding new ways for his compositions to evolve, catching you off guard when you think you have them figured out.

His guitar solos often do what his vocals could not, acting as an extended hand to pull you into the complex thoughts and mixed emotions behind the words. In “1,000 Eyes” he describes “a newfound age of advanced observeillance” that sounds a little like life online in the 21st century, but his scorching leads are what makes you feel it: the paranoia, the instinct to burrow inside yourself, the dream of breaking free.

With every album, Schuldiner found a different group of musicians to complement his latest direction, and you can’t talk about Symbolic without talking about drummer Gene Hoglan. The Dark Angel virtuoso has jokingly credited himself with playing “lead drums” on the record, but it’s a testament to his gift as an accompanist that his playing—sometimes sounding as if he’s written a different part for each 15-second segment—never feels distracting or showy. Alongside bassist Kelly Conlon and guitarist Bobby Koelble, he finds a balance between technical skill and pure instinct that fits right within the world of Schuldiner’s songwriting.

“My hands are jazz, but my feet are metal,” Hoglan said at the time, speaking both to the thought behind his performances and the layers in Schuldiner’s songwriting. What Hoglan was literally referring to is the contrast between the blastbeats—a staple of extreme metal, with constant, undeterrable motion against the kick drum—and the cymbal work, which is lighter and trickier than what you might typically encounter in the genre. But you can also attribute his concept to Schuldiner’s songs themselves: an eruption below, a calm on the surface.

The concentration on this aspect of Schuldiner’s songwriting helps distinguish Symbolic from the rest of Death’s catalog and most death metal of its era. Plenty of bands have aspired to write riffs like the ones in “Zero Tolerance,” but few could dream of replicating the delicate, visceral thread connecting one part to the next. While classics from the era like Cannibal Corpse’s The Bleeding or Deicide’s Once Upon the Cross seem intentionally claustrophobic—relentless records that fill a small space with as much sound as possible—these songs constantly find ways to open themselves up. “I like to look my audience in the eyes,” Schuldiner once said of his live performances, how he tended to avoid the customary hair-in-the-face headbanging. On Symbolic, you can hear him gazing toward the crowd, trying, at every turn, to make a connection.

The sense of humanity is partially why Symbolic has endured as a death metal classic, an evergreen gateway to the genre Schuldiner was consciously trying to abandon. It is neither his most groundbreaking album nor his most technically impressive, but it is the one that makes the most room for newcomers, whose mysteries offer the most depth for repeated listens. In some ways, these songs trace a journey from the classic rock that Schuldiner grew up on toward the niche community he found himself leading as a young adult. When asked about the inspiration for the use of acoustic guitar throughout the record, he proudly cited inspiration from his childhood heroes Kiss—the band that first made him fall in love with the instrument.

Back then, music was a sanctuary for Schuldiner. His parents bought him a guitar as a coping mechanism after the death of his older brother, Frank, who was killed in a car accident. Chuck was 9 years old at the time, and, bored to tears at lessons trying to learn “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” found new inspiration once he plugged in. “The first time he played the electric guitar, it was as if a switch was turned on in him,” his mother recalled. “And it never turned off.” For much of his life, this intimate connection made the roadblocks he faced—bandmates who didn’t share his devotion, journalists who fed into rumors about his personal life, industry people glomming onto trends—feel unbearable, a grim corruption of something pure.

Schuldiner intended Symbolic to be the final album he released under the Death banner. He felt fed up with the genre, confined by its boundaries, and he saw this album as the culmination of his work to that point. The first step was to lose the band name, which now felt like an unfortunate tattoo from his youth. His next project would be called Control Denied, and he would finally enlist a vocalist who could sing melodic leads. Instead of following his instinct, however, Schuldiner was roped into making another Death album—the label was concerned it wouldn’t be able to market his music without the brand name—and his dream was put off a few years.

Before his death from brain cancer in 2002 at the age of 34, Schuldiner’s final releases were one last Death album—1998’s proggy, brilliant The Sound of Perseverance—and one album as Control Denied—1999’s underrated The Fragile Art of Existence. Each project built on aspects from Symbolic—its nuanced lyrics, sharper melodies, and refusal to be boxed in—and continued widening a path for other artists in the genre. To this day, Schuldiner remains a figurehead for heavy bands known for shapeshifting—from the totemic death metal of Philadelphia’s Horrendous to the astral projections of Denver’s Blood Incantation—while staying true to the genre’s initial mission of lawlessness, constantly challenging perceptions.

In the 2016 documentary Death by Metal, producer Jim Morris reveals that Schuldiner considered an alternate way forward during the sessions for Symbolic, which were longer and more elaborate than any of their previous albums. It was the first time they demoed material with an 8-track recorder, allowing the band to perfect their parts before heading to the studio. The goal was to refine each song, zeroing in on the most immediate qualities of Schuldiner’s writing. “How do you put more melody into his music? Well, you can’t do it with the guitars, he’s already really, really melodic,” Morris says. In response, Schuldiner tried a cleaner style with his vocals: “I’m like, ‘Oh my god, you can sing,’” Morris recalls. “You’re great!’”

With the timid excitement of brushing upon a friend’s secret, Morris suggests the two briefly imagined a different version of the album with Schuldiner singing in a more traditional style, but they never recorded any of it. It’s tantalizing food for thought, but in the end, their instinct was right. If Death’s previous work offered a blueprint for what the genre of death metal can be, then Symbolic offered a way to exist and evolve gracefully within its borders. There are plenty of albums where a band crosses the threshold: reaching for a wider audience and finding them, firing on all cylinders and ascending to the next level. Symbolic is something rarer: a visionary artist desperate to push forward, raging against his limitations until it sounds a little like celebration.

0 comments:

Post a Comment