Today on Pitchfork, we are celebrating the messy, game-changing, era-defining genius of the Wu-Tang Clan with five new reviews: two albums, two solo projects, and a film score.

The drums on “The Faster Blade,” the third song from Ghostface Killah’s 1996 debut, Ironman, come from a song called “El Rey y Yo” by the Chilean band Los Ángeles Negros. The lift is direct, uncomplicated; RZA adds some body to the low end, but the pattern is unchanged. The new beat finds its melody, however, in a vibraphone borrowed from the Persuaders’ “Can’t Go No Further and Do No Better,” a plea from one lover to another to work through their problems. “The Faster Blade” strips the sound of its tenderness, repurposing it as a warning: Whatever sweetness remains in the world is about to be swallowed whole.

The mutation suits Raekwon, who raps about locking down the cocaine trade in coastal Georgia, ripping off his Korean suppliers, arranging murders for hire from remote British territories. It’s the sort of pulp crime—meted out in bursts of improvised slang and girded by Five-Percenter moralism—that he and Ghost had perfected on Only Built 4 Cuban Linx, Rae’s monumental debut from one year prior. But when his verse ends (“All my Spanish niggas love us/We movin’ like Russia, bone crusher/At the flick, stick the usher”), Ghost is nowhere—the song is simply over. Just two tracks later, on “Assassination Day,” RZA’s instrumental is taunting in its sparseness; he, Rae, Inspectah Deck, and Masta Killa trade verses about stalking enemies “like prey” and the devil “poisoning the birth water,” the blurring of lines between literal and metaphysical, criminal codes and animal chaos that are tenets of Ghost’s writing. Yet once again, the headliner is nowhere to be found.

These absences had precedent on Wu-Tang records: Cuban Linx’s “Wisdom Body” is a solo Ghostface song. But where that was a creative decision (Rae, Ghost, and RZA agreed that Ghost’s extended pickup attempt would seem more unnervingly intimate if left alone), these new ones were symptoms of a yawning depression. Between Wu’s 1993 debut and the release of Cuban Linx, Ghost, then in his mid-20s, was losing weight and suffering headaches and blurred vision. By the time he was diagnosed with diabetes, his drinking had gotten so bad that RZA was patching together disparate vocal takes to work around Ghost’s frequent slurring. And in the spring of ‘96, his best friend was arrested for a murder he did not commit. “I couldn’t write to those records,” Ghost told Billboard last year, referring to tracks his collaborators had prepared for him. “I couldn’t come behind that, not feeling how I was feeling.”

Recorded in that fog and against a deadline—the last one he would ever accept from a record company—Ironman captures a Ghostface who is scattered, overflowing with angst, lashing out. Where on Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) he wrote concentrated bursts of athletic threats or longer, mostly linear reflections, here his internal logic is scrambled, the syntax shifting, time an afterthought. But this fragmentation is a natural complement to his written and vocal style. Whatever sorrow or delusion bleeds through the mix ends up making the rapper seem like a method actor, whipping himself into such a frenzy that he can convincingly render a world where there is a bag of cash sitting in the trunk of every bait car, an assassin in every vestibule. Over scythelike RZA beats that recall the Blaxploitation films of the 1970s, Ghost recreates the New York underworld of his adolescence in impressionistic fits.

The idea for the Blaxploitation riff came from RZA, whose creative whims dictated every Wu release he helmed. Working first from his estate in Ohio, the Abbot played Ghost beats over the phone: Al Green’s God-fearing “Gotta Find a New World” morphed into an impish bounce on opener “Iron Maiden.” Bob James’ “Nautilus,” a staple sample for rap producers dating back to the late ’80s, is made to sound, on “Daytona 500,” as if it’s gasping for its first breaths. The palette is loose and hooky, and it underlines Ghost’s humor. It also lowers the album’s stakes, at least in the early going. If Cuban Linx was a sweeping epic, Ironman is The Mack: lean and vulgar, irresistible all the same.

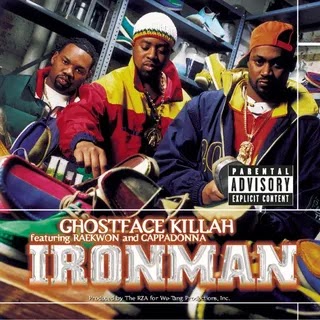

The New York that Ghost and Rae (and Cappadonna, who receives prime billing and appears on the album cover) imagine is icy and intermittently forgiving. The album came out at the end of October, and its scenes are largely set in winters that are broken up by short trips to the Caribbean or Hawaii, where middle-class drug runners sip “mixed drinks out of broke coconut bowls” and trudge through slush on their way home from JFK. Ghost’s verse on “Motherless Child,” the cleanest distillation of the album’s concerns, crescendos to a rich young dilettante-hustler being killed during a robbery of his $5,000 King Tut necklace; one of his assailants’ puffy Guess outfit might suggest a bulletproof vest underneath, while the other’s Pelle Pelle certainly hides a gun.

Raekwon’s numerous guest appearances do not make him quite the co-star Ghost was on Cuban Linx, but he adapts well to the lighter fare. One of his many gifts as a writer is to pack familiar patterns with so much idiosyncrasy that they feel wholly new. This is true when he’s dispensing straightforward wordplay on the wrong half of a bar (“Slide on these niggas like a fresh pair”), packing layered insults and odd imagery into seemingly overdetermined rhyme schemes (“No, you won’t play me like your lady/Pay me 380, spit it at you like a baby”), or sinking into the beat as if it were quicksand, as he does on “260” when he raps, “We walked in, both of us, looked like terrorists.” Cappadonna appears a comparatively modest five times and might be even more impressive—especially for his turn on “Camay,” where his “heart was racing like the hands on the clock” as he leaves a seduction on a tantalizingly ambiguous note.

But Ghostface is one of the most inimitable writers New York has ever produced. His verses, like the vignettes within them, double back over themselves with plots intersecting or evaporating entirely. Momentary glimpses into his childhood (from “After the Smoke Is Clear”: “They used to push me in shopping carts”) read, initially, as myth. The silliest images, like Kiana’s girlfriend Wanda—the one with a cream Honda and legs like Jane Fonda—are precisely drawn. His understanding of the supreme mathematics short circuits the slot machines at outer-borough racetracks; he inhales smoke on the floor of a steel mill just to exhale it at his enemies. These threads of memory and imagination coil around each other in the text as they do in our brains.

Even when something obvious seems to jut out, it’s quickly qualified with asides—or with plausibly deniable threats. “Poisonous Darts” is a typically breathless pair of verses from Ghost, but transforms in its final five seconds. “My heart is cold like Russia,” he blurts, a line so simple it scans as a real revelation. But he continues: “Got jerked at the Source Awards/Next year, 200 niggas coming with swords.” The picture of the Paramount Theater rushed by medieval warriors with chain mail and opinions about MC Eiht muddles time and context as amusingly as when RZA uses a whole verse, on “Smoke,” to move from Staten Island to the Punic Wars.

That reflex—to smash stories about his own life into a thousand splinters—obscures any hint of real autobiography. But Ghost does not flinch when he sketches other characters. “Wildflower” is wickedly angry, rapped from the perspective of a scorned lover berating his ex. Whether or not you believe it was Ghost’s intent, the song plays with a knowing wink: It becomes a self-portrait of pettiness at some point between the wistful remembrance of the time the speaker “broke your ovary” and when he gets indignant about having introduced you to the films of Robert De Niro. Or take Juanita Cash Hawkins, the woman Ghost introduces, on “Camay,” who’s half-Hawaiian and works at a law firm on Fifth Avenue, “three blocks from the Gucci spot.”

There is a notable exception to his tendency to hide the personal. On the album’s lead single, the Mary J. Blige-assisted “All That I Got Is You,” Ghost’s writing turns completely naturalistic as he recounts growing up with 15 people packed into a three-bedroom apartment, being asked to carry notes that begged for food to neighbors who might not have any, caring for two brothers with muscular dystrophy. On a song that is so sentimental, Ghost’s picture of his mother is surprisingly evenhanded. He remembers her buckling under the weight of his father’s disappearance; he remembers her wiping the crust from his eyes before he left for school. Case workers lurk like undercover cops, or poltergeists.

It’s fitting, given both the uncanny state of commercial music preservation and Ghost’s own crypticism, that the album’s most representative song is not available on DSPs or new pressings, presumably due to sample clearance issues. “The Soul Controller,” Ironman’s original closer, is built around a Force MDs rendition of Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come.” But where Cooke’s song elegantly reduces civil rights issues and spiritual reckonings into tidy verses, “The Soul Controller” lurches and sprawls like the paranoia that snaked through the decades following Cooke’s death. “I don't know what’s up there/"In that great big ol’ sky” becomes less mystical, applying instead to the “UFOs” Ghost raps about—“Faces you never seen before” roaming the halls of your buildings, undercovers or out-of-towners. By the song’s parameters, the upper limit on success is you and your friends splitting a house in “the white part of Queens,” while hell is “being watched all day like enemy’s prey.”

The arc of this story is supposed to be: Brilliant artist hits bottom, pours anguish into work, overcomes. Instead, things got worse. The year after Ironman’s release, Ghost’s best friend—the one arrested for murder—would be convicted and sentenced to life in prison. (Grant Williams was paroled in 2019 after serving 23 years of his sentence. Last year, that sentence was vacated following a review of the case that uncovered eyewitness testimony exonerating him.) His diabetes worsened, and he moved to a tiny village in Benin to seek alternative treatment. When he returned to the States, Ghost had to do a bid of his own—four months on Rikers Island for an attempted robbery outside of a club in Manhattan. It was around this time that the FBI started investigating the Wu as a gang whose true purpose was not music, but whatever could conceivably fall under the scope of the RICO Act.

After surviving Rikers and gaining control of his health, Ghostface finally finished his masterpiece, Supreme Clientele, which was released in February 2000—long after it was promised; no deadlines. With that record and a handful of others (2006’s Fishscale and the leaked advance of Bulletproof Wallets chief among them), Ghost’s career seems to reject the notion that the dire circumstances under which Ironman were recorded are necessary for him to write or rap well. Federal agents and the ghosts of friends haunt his later raps, but their evocations feel literary. On Ironman—a record that is mired in, rather than about, this psychological torment—they’re tangible forces to be looked directly in the eye.

0 comments:

Post a Comment