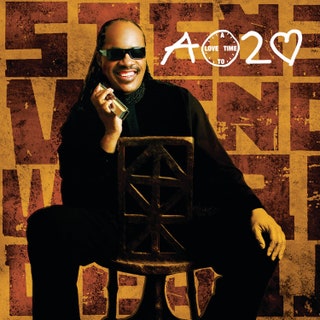

Today on Pitchfork, we are celebrating the artistic bounty of Stevie Wonder with five new album reviews that span the breadth of his remarkable career.

For an artist who had spent each decade of his life in the public eye, the years leading up to Stevie Wonder’s 77-minute opus, A Time to Love, were uncharacteristically fallow. Steeped in intrigue and plagued by delays, the album’s decade-long development became a story in itself. Though Wonder had long led the way in studio innovation, it appeared the infinite possibilities of the digital age, combined with his notorious tendency for tinkering, had finally begun to overwhelm him. Twice, hard deadlines came and went. Deep tensions formed between Wonder and his longtime label, Motown, who was pouring resources into the recording and counting on the results to help buttress its flagging bottom line.

Sylvia Rhone, Motown’s newly appointed president, was eager to put the label on a more modern footing, and her simmering frustrations with Wonder soon became public. “In time, God will give me what I need to do the album on time,” he told the press, a fairly open-ended, mystical formulation unlikely to comfort stakeholders. Meanwhile, the credits stretched to include everyone from Prince to Paul McCartney, India.Arie to gospel singer Kim Burrell, and even his own daughter Aisha Morris. Wonder had long enjoyed the company and energy of bountiful collaboration, and all these choices made sense with respect to conjuring a career-spanning aesthetic throughline, but the inevitable scheduling conflicts only further complicated the process.

Process was only part of the distraction. When Wonder’s previous LP, Conversation Peace, was released in 1995, he had graduated from a celebrated musician to something on the order of a cultural deity. As boomers came of age and consolidated political and economic power, the music of their youth was increasingly detached from its context and recycled as nostalgic comfort food: Picture Bill and Hillary Clinton capering to “Don’t Stop” at the 1993 inauguration party, or the historical white-wash of 1994’s Forrest Gump. Try as he might, Wonder struggled like many of his peers to unyoke himself from the cultural forces determined to reduce the radical achievements of the ’60s and ’70s to a passive, self-gratifying soundtrack.

In spite of the crass cheapening of the ’60s tumult, Wonder continued to throw his shoulder into righteous activism. His involvement in the USA for Africa project and the campaign to make Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday a national holiday during the 1980s affected lasting and meaningful change. As other avatars of dissent from the previous era lost interest or principle, Wonder’s steadfastness elevated his reputation ever higher. He traveled the world and was greeted like a foreign dignitary. He was feted with awards and performed at the 1999 Super Bowl. Ten fraught days after 9/11, he played harmonica on “America the Beautiful” during what was essentially a nationally televised wake, accompanying Willie Nelson, one of his only true peers as a chronicler of the overlooked and underserved.

Additional complications abounded in Wonder’s personal life, long a Gordian knot of shifting romantic allegiances that eventually resulted in his fathering nine children with five women with whom he was on variously good terms. There were palimony cases and sundry disputes, and the threat of a tell-all book from a former backup singer that mercifully never appeared. Most painful of all was the 2004 death of his first wife and longtime creative partner, Syreeta Wright, which shattered him to his core and inspired the lyrics to the A Time to Love track “Shelter in the Rain.” (“When all the odds say there’s no chance/Amidst the final dance/I’ll be your comfort through your pain.”) This rich tapestry of backstory was widely reported in the music press, fomenting genuine curiosity about what bounty A Time to Love’s seemingly endless gestation period would ultimately produce.

When the first single finally materialized in the spring of 2005, it seemed like all the waiting had been worth it. “So What the Fuss,” featuring Prince on guitar and En Vogue on backing vocals, is a forceful piece of socially conscious funk, with Wonder’s growling vocals and distorted clavinet convincingly conjuring the mood of early ’70s classics Innervisions and Talking Book. Sounding like the ecstatically fried grooves of Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain experiencing the aftershocks of Prince’s own “Housequake,” “So What the Fuss” simmers with a mix of gospel uplift and lurking menace, always the secret undercurrent of Wonder’s best work. Without an official release date for the proper album, Wonder seemed to relish the rough-and-ready vibe, even vetoing Motown’s first choice for a single, the rather mawkish “From the Bottom of My Heart.”

While Motown’s choice for a single wouldn’t have elicited the same excitement, it would have been a more accurate representation of the work to come. When the album was finally released that fall, it was 77 minutes of unerringly stately, sometimes bracing, and occasionally indistinguishable forays into neo-soul and quiet storm, taking love in all its permutations as an overarching theme. After a lost decade, A Time to Love was abundant proof that Stevie Wonder had endured. And yet, it desperately could have used some editing—it’s at least 20 minutes too long. Or perhaps it should have been two very good Stevie Wonder records, rather than one overstuffed omnibus. But genius works in mysterious and sometimes convoluted ways, and these comforting, contented odes to lasting love feel like an act of generosity and an exercise in unvarnished sentiment.

After the long wait, the delays, and the intense build-up, Wonder’s return was neither late-career miracle nor shell-of-his-former-self parody. Instead, it was an earnest overview of the artist in middle age. Opening track “If Your Love Cannot Be Moved,” a salsa-inflected duet with Kim Burrell, spans six leisurely minutes. Its supple groove and genre fusion seem intentionally designed to reassure listeners that Stevie Wonder, the peerless bandleader and arranger, remained very much in control of his gifts. If anything he may be too much in control. “Sweetest Somebody I Know” is a charming grab bag of go-to-Wonder-isms from the Hallmark-adjacent sentiment to the harmonica solo: It’s lovely to listen to, if light on inspiration. So it goes for much of A Time to Love’s slow-burning first half. “Moon Blue” is pretty but a touch perfunctory to justify its near seven minutes. The title of “From the Bottom of My Heart” pulls its refrain from his ’80s smash “I Just Called to Say I Love You” but fails to improve upon it. It isn’t remotely fair, but is nevertheless inevitably the case with an artist of Wonder’s stature: In his fifth decade of recording, his primary competition was his younger self.

If A Time to Love never quite blows you away, there are still glimpses of Wonder’s sublime ability. The gorgeous duet with daughter Aisha Morris, “How Will I Know,” harkens back to his grounding in the jazz standards of the pre-rock era, conjuring the heartbroken balladry of Billy Strayhorn. “My Love Is on Fire” features a buoyant keyboard hook and robust libido à la the ecstatic horndog loverman jams of 1972’s titanic Music of My Mind. The penultimate track, “Positivity,” is a vaguely silly but ultimately irresistible paean to the profound optimism which has been a lifetime trademark of an artist born into the twin adversities of blindness and poverty. Conjuring a winsome vibe liberally borrowed from the Ohio Players’ “Love Rollercoaster,” Wonder continues asking the big questions: “When the people ask me as an African American/What do I see tomorrow in the human plan/Is it possible for all of the people of the world to co-exist?” His answer is hedging, circumspect, but ultimately hopeful.

At its best, A Time to Love uses its self-referential sprawl to convey the wisdom of a man who’d seen it all. He was no longer the prodigy who helped make Motown an institution, or the visionary shaman of ’70s soul, or the go-to hitmaker of the go-go ’80s. The world keeps on turning, and Wonder changes with it. This music was also an endpoint, at least for the time being. Following the record, Wonder essentially went dormant again. Suffering from health problems that required a kidney transplant, he released no new music for 15 years. Then, in 2020, he surfaced with two singles, released on his own label. Even if the unimpeachable masterpieces are behind him, A Time to Love proved his presence can still elevate us to higher ground. If Stevie Wonder hasn’t given up, then why should we?

0 comments:

Post a Comment