In his 1978 essay Sound Poetry: A Survey, poet Steve McCaffery traces three distinct eras of the field. He notes the first “paleotechnic” period as defined by chant structures—think nursery and jump-rope rhymes. Later came the Dadaists and Futurists, whose desire to split words from semantic meaning allowed for a focus on their acoustic properties. Then the tape recorder arrived, allowing practitioners to work beyond the human body’s limitations. Sound poetry, he asserts, is about feeling the insufficiency of language and, as a result, finding new possibilities of expression. A concluding declaration is at the heart of his text: “[Sound poetry] is, above all, a practice of freedom.”

Asha Sheshadri’s music displays a rigorous consideration for the way that technological practices can rupture language to create something original. She’s strikingly different from many of her sound-art peers, the kind who’ve spent the past decade using spoken text in diaristic modes or as a way to approximate ASMR videos (a phenomenon that has often ignored its sonic precedents in sound poetry, radio plays, and acousmatic music). On her 2020 epic “Patty Live June,” she uses field recordings, shapeshifting electronics, and text recitations to explore the psychology of Stockholm syndrome. Across Misfired Empathy, her collaboration with brainy prankster Jack Callahan, any speech we hear is regularly mangled to create conflicting emotions. She pushes her practice further with Interior Monologues, a solo album that features her most compelling use of singing as a phonological, textual, and conceptual launchpad.

In previous works, any singing Sheshadri employed had a largely textural impact. Under the Isolde Touch moniker, reverberating vocals recall artists like Julianna Barwick. In Open Corner, her duo with Christian Mirande, fleeting melodic moments are just one element in a robust sound collage. Throughout Interior Monologues’ 29 minutes, she sings Joni Mitchell’s “Help Me” with a tender casualness—the sort of vocalizing that only barely breaches the talking/singing threshold, and has the semblance of someone puttering around at home. Her edited, overlapping, and non-chronological mishmash of verses creates a technology-produced simultaneous poem, and the effect is evocative. It’s easy to identify the loping melodies of Mitchell’s lines “Oh, didn’t it feel good?” and “When I get that crazy feelin’” as deeply lovestruck. But as Sheshadri repeats Mitchell’s words, a palpable sense of anxiety comes to the surface; found sounds and stuttering samples reinforce the impression that this is an illusory moment frozen in time. One spoken line sums up the mood: “Three hours of total disbelief.”

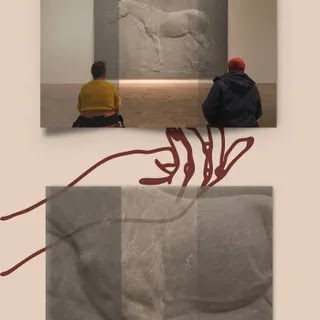

This focus on the temporary is highlighted by the album cover’s lightly edited images of Charles Ray’s Two horses (2019). The piece exemplifies what the sculptor once said about the medium: “A sculpture physically ages as it slips into time. Authorship, context, and content fade away long before sculptural stone turns into sand.” It’s no coincidence that the Court and Spark highlight is the song Sheshadri wields here: Its lyrics reference “I’m a Rambler, I’m a Gambler,” a traditional American folk song that has been interpreted by Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. When the second half of Interior Monologues tightens the focus on this pairing of recited text and song (and even includes moments when the former turns into singing), Sheshadri embraces the inevitability of contextual dissolution. Musings on Two horses and the impermanence of one’s cultural footprint are revisited with slight variances, and they have the effect of gradually repurposing what Mitchell’s words mean. The refrain of “Help Me” (“We love our lovin’/But not like we love our freedom”) is initially a sobering reality check about a doomed romance, but near Interior Monologues’ end, the “freedom” Sheshadri sings of feels related to something else entirely: the impossibility of fully understanding art in their original contexts. Find joy, she seems to suggest, in how unavoidable ignorance always births something new.

Sheshadri’s music is clearly indebted to sound poetry forebears like Henri Chopin, Marran Gosov, Larry Wendt, and text-sound composer Åke Hodell. But her music has a propulsive energy that embodies the entirety of sound poetry’s progressive spirit and complex history, one that McCaffery found challenging to discuss because of its competing but related concerns—“attempts to recover lost traditions” and “attempts to effect a radical break with all continuities.” The most striking result is that Interior Monologues then points to the beauty of all art as a prismatic culmination of exchanges across different generations and cultures. In theory and practice, Sheshadri’s music reminds us that everyone can and does participate in this never-ending dialogue.

0 comments:

Post a Comment