Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit the 1997 album from a hype-man turned MTV star whose kinetic flows and boundless energy electrified the world of ’90s hip-hop.

The track didn’t bang or knock. It tiptoed. It wiggled. When Busta Rhymes first heard it during the recording sessions of his second solo album, it was unlike anything he had ever rapped on: sinuous, low-key, minimal. A former rapper named Shamello found the sample—a high-calorie AM-radio confection called “Sweet Green Fields” by Seals & Crofts—and his partner, Buddah, sheared off the soft-rock blubber, leaving behind only a single twitching muscle.

Busta must have glimpsed his future in the song, even if he was unsure how to rap on the beat without trampling it. A “Busta Rhymes verse,” up until now, had meant limbs flailing, eyes bugged, spittle spraying. He’d become famous for roaring like a dungeon dragon, both with his teenaged group Leaders of the New School and on countless posse cuts and cameos, but this seemed to require a different approach. It was Puff Daddy who gave him the advice he needed: Calm down. Don’t scream. “You alienating the girls, playboy,” he advised. Nobody wants to dance up close to a dungeon dragon.

Consider that Busta Rhymes thinks of “Put Ya Hands Where My Eyes Can See”—one of the most antic hip-hop songs ever, a riot of cross-rhythm and color and jibbering end rhymes—as his “calm” song. He found its success disorienting: “Do I need to get caught up in doing all my records calm?” he asked genuinely on VH1’s Behind the Music. This should give you a keyhole glimpse into Busta’s struggles as he endeavored to have what no one in his position ever had: a career. As a protégé of Public Enemy, Busta watched Flava Flav, perhaps hip-hop’s greatest hype man, up close. He was all too aware of the fate of a hype man without a foil: By 1991, Flava had lost custody of his children and was sinking into addiction. By 2000, he would be scalping Yankees tickets for extra cash. The lesson wouldn’t have been lost on Busta; The guy who riles up the crowd gets left out in the cold.

To hear Busta tell it, he never wanted to be on his own. For years he’d been happy trading lines and high-kicking with his friends Charlie Brown and Dinco D, the other members of Leaders of the New School. Busta met Brown and Dinco in high school shortly after his family relocated from Brooklyn to Long Island, and together with Busta’s cousin Milo as DJ, they started playing local parties and skulking around 510 South Franklin Street, the headquarters of Public Enemy, hoping to get noticed. Finally, Chuck D took them under his wing and began to school them, drill-sergeant style—he used to make them run while rapping, just to test their endurance and commitment.

Busta had already given everything he had to the group, dropping out of school at 17 to record their first album. His father, an electrician, disapproved of his son jumping around and yelling for a living, but Busta was all-in. When his high-school girlfriend got pregnant, the band kicked into high gear, running from one sweat-soaked show to the next all over the five boroughs, sometimes racking up two or three a night. Success was the only option, but Busta had his brothers. “Suffering with a team, y’all can still help be each other’s support system,” he mused once. “Suffering on your own…that’s a whole ’nother ball game.”

But Busta’s charisma had other plans for him. He had a body that moved as if jerked by wires, a megawatt smile that cameras drank up. He was one of six flailing rappers onstage on the Arsenio Hall Show when A Tribe Called Quest performed their hit “Scenario,” and he didn’t even make his way onto the couch for the interview afterward. Nevertheless, he was the only guy anyone remembered, leaping around in stripes and turning his hat inside out as if to produce a rabbit.

Eventually, his charisma won: Demand for solo Busta became so constant and exhausting that it crowbarred the group apart. Charlie Brown, fed up with being an also-ran in the group he started, essentially quit Leaders of the New School on live television during a Yo! MTV Raps interview in 1993. Busta waited outside Brown’s apartment for hours, begging his bandmate to rejoin. Brown never came down to speak.

Thus, one of the longest and most prolific solo careers in rap began out of lonely necessity. As 1994 rolled around, Busta Rhymes had no group. Two years earlier, his baby had died after premature birth, and his second child, T’Ziah, was still in diapers. Busta was going to have to be a solo artist, and he would have to figure it out as he went. When he signed with Elektra Records and went into the studio, it took him a humiliating seven months for inspiration to kick in. When it finally arrived, it was from some of the earliest recorded rap music: The Sugarhill Gang’s “8th Wonder,” with Big Bank Hank’s ebullient refrain of “Woo-Hah! Got you all in check.” The song’s preternatural innocence unlocked something, reminding him of the disco on the radio in his East Flatbush youth.

”Woo-Hah! Got You All in Check,” his debut solo single, went platinum in about a month, based largely on the Hype Williams-directed video. Without Williams, it seems fair to say, there might never have been a solo Busta Rhymes. But the reverse might also be true. Before Busta, Williams was a journeyman, bringing better-than-average filmmaking chops to unremarkable clips by acts like Positive K and Blackstreet. Busta seemed to shake something loose in him. Beginning with “Woo-Hah,” Hype Williams videos became, well, Hype Williams videos—color palette by Dr. Seuss, low angles and flying fists courtesy of Marvel comics. It’s one of his first uses of the fisheye lens, which soon became his signature. With one video, Hype Williams instantly became an auteur, and Busta was his first muse.

But “Woo-Hah” was not a career plan. “Woo-Hah” was the three-minute exhilarating yawp of a class clown who has just locked the principal in the janitor’s closet. It was like Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s “Shimmy Shimmy Ya” or Flava Flav’s “911 Is a Joke”—a wild card’s brief foray into the sun. What is the game plan, an exit strategy, for a guy like this?

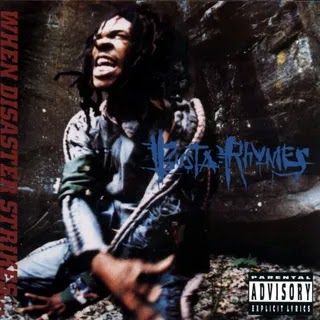

”Put Ya Hands Where My Eyes Can See” was the answer. Released in August 1997, the track hit No. 2 on the Hot R&B/Hip Hop Songs and helped When Disaster Strikes… go platinum in about a month. In the video, also directed by Hype Williams, Busta sported red leopard print and accompanying face paint in front of a blood-red curtain. Dancers in full regalia seemed to wind themselves up and down to the time of the irregular beat. It was Busta’s tribute to Coming to America, which was playing on mute in the studio during mixing.

If he played the jester on “Woo-Hah,” on “Put Ya Hands” he was the ringleader. His flow, spry and slippery, sounded like someone chuckling to themselves. In “Put Ya Hands Where My Eyes Can See,” you can hear a dungeon dragon learning to purr.

Today, the rhythmic tattoo of “Put Ya Hands” is a piece of hip-hop history, as instantly recognizable as the “Shook Ones Pt. II” beat or the “Apache” break. Syleena Johnson sampled it in 2001, inviting Busta and the rappers comprising his Flipmode Squad for the remix. When JAY-Z and Beyoncé wanted to telegraph their status as Black royalty on 2019’s The Lion King: The Gift, there was only one song to reach for: “Mood 4 Eva” interpolates the sample and Jay and Bey pay homage to the video. In 2018, a young rapper named Snowprah broke out of New Haven, Connecticut with an exuberant street anthem called “Yank Riddim.” As she ran through the streets of her neighborhood, waving a Jamaican flag, the “Put Ya Hands” beat twitched in the background. Busta grew up in a household that revered reggae music; now he had put his name on a modern-day riddim.

The next big single from When Disaster Strikes… repeated the formula for “Put Ya Hands,” but went bigger. Rashad Smith, the same producer who flipped a disco-rap record for him on “Woo-Hah,” gave him “Dangerous,” a flip of an electro record. The accompanying video (Hype Williams again) parodied Lethal Weapon this time, another film that, like Coming to America, always seemed to be playing somewhere on television. For good measure, they threw in a brief scene of Busta dressed as Sho’Nuff from the kung fu blaxploitation flick The Last Dragon. For years, everyone was telling Busta Rhymes he was a superstar, and on MTV, he finally found his perfect medium.

The camera loved Busta Rhymes, and he loved it right back. He was made for another generation when technologies were more primitive so the personalities had to be bigger. Even his tip-toe flow has something emphatic about it, like a silent movie actor. Embracing his mascot status among MTV video programmers, Busta carved out his role within mainstream rap. He was the trickster, the pop of color, the light that threw the dark into relief. A hype man again, in other words, but this time for all of hip-hop.

Over the next four years, Williams and Busta would churn out several versions of this video. On “Gimme Some More,” he paid homage to Merrie Melodies cartoons over Psycho strings. On “Fire,” he got swept up by a CGI tornado. In Janet Jackson’s “What’s It Gonna Be,” he imitated the liquid-metal robot from Terminator 2 (the video’s price tag, reported around $2.5 million, made it one of the most expensive of all time.) None of them matched the visual wit of “Put Ya Hands Where My Eyes Can See,” but they helped turn Busta Rhymes into a universally beloved household name, a rapper with ironclad cred your mother might recognize.

If he was flashy on MTV, the Busta Rhymes of his studio albums has always been humbler. Who was Busta Rhymes without a camera, in the harsh light of 17 or 18 tracks? What else could a calmed-down dungeon dragon do? His first three albums tried to find the answer in apocalyptic imagery, at a time when major-label rap mostly concerned itself with celebrating and guarding material success. His debut, 1996’s The Coming, hinted at themes of rapture, and on the intro to When Disaster Strikes..., we are warned of a cataclysm that will scour the Earth. “Store your food!” a voice bellows. His next album, 1998’s Extinction Level Event, would take the apocalypse theme even further, with monologues about the slow death of the human race interspersed with his usual slate of party bangers.

It was an unusual fixation for a class clown, but Busta was raised in a Seventh-Day Adventist home, a sect of Christianity with a literal interpretation of the Second Coming. (He gave up the religion as a young man when he discovered the Five Percent Nation, but he never lost his fascination with end-of-days: Along with Method Man, Busta was one of the most enthusiastic believers in Y2K.) Perhaps because he was backed into his career out of desperation, there’s always been a ticking-time-bomb sense of paranoia and doom lurking in Busta’s party music. He rapped—and entertained—like he was certain the wheels were minutes from falling off. His intimation of apocalypse might have just been his own flop-sweat writ large. One question hovered over every album: “How long can I keep this up?”

No matter the skits, album covers, or packaging, Busta Rhymes songs remain primarily receptacles for Busta’s inexhaustible energy. He’s a hypertechnical MC, with a grab-bag of flows and cadences so bottomless that he seems to hear six potential songs in each beat. He played drums as a kid, and when he auditioned for Chuck D with Leaders of the New School, he played the kit while Charlie and Dinco D rhymed. “My flows got so much rhythm, substitute the drummer,” he spits on the first verse of “The Whole World Looking At Me,” and no rapper has ever rapped more like a percussionist. The freedom and joy of Busta’s rhyming came from a sense that he could pick up any part of the beat, any pattern, and run with it as far as he wanted to. In his mouth, words aren’t words—they’re snare heads.

The flip side of this is that when you examine his words on a page, you’re sometimes left with a transcribed drum solo. For every line that squiggles beautifully across your eardrum—“Ha-ha, laugh at ya, oh, me and my passengers/Flip-ass niggas over quick like frying pan spatulas,” from the title track”—there is a clunker like, “While you coughing I be flossing like a fucking dolphin,” or a puff of hot air like, “Rhymin’ Rastas eating enough exotic pasta.”

The best songs on When Disaster Strikes... don’t try to burden Busta with irrelevancies like concepts, narratives, guest hooks, or context. “Rhymes Galore” gives him a rubbery sample and a canvas bright enough to suit him, and then clears the decks. Over a flip of Rufus Thomas’s “Do the Funky Penguin,” he pogos off every available space, saying—what? Nothing, anything, everything. He yells “Jumpin Jehovah’s Witness” and rhymes “ampere” with “chandelier.” The hook—“Rhymes galore! Rhymes galore! Rhymes galore!”—is also the message. It hints at the anarchic album artist he might have been, more intriguing and subversive than what he eventually became.

Rap was growing darker, lonelier, the stakes getting higher. The consummate survivor, Busta was intent on keeping up, so he got tougher. On “Things We Be Doing for Money,” Busta does his best version of Life After Death-style street opera, full of merciless bloodshed and bodies left in the streets. The Mobb Deep-style gloom of “We Could Take it Outside” is convincing, but there’s something dispiriting about it; Busta Rhymes threatening to bash in your head was about as much fun as being juxed by Bugs Bunny.

In the second half of the ’90s, rap was approaching terminal masculinity. It might be hard to imagine today, when people like Young Thug casually wear dresses on their album covers and one of the biggest stars in hip-hop is out, but back then, Busta was the only male rap star willing to play with gender lines. Everyone in Hype Williams videos was dressed in bright colors, but Busta was unafraid not only to dress in bright colors but act like he was dressed in bright colors—he was the only one willing to dance, move, gyrate, smile wide enough for toothpaste commercials. His gender play was surface level, strictly vaudevillian—in fact, he’s shown a long and nasty streak of homophobia—but in 1997 he was the only one willing to get on stage in a dress next to Martha Stewart.

Today, Busta Rhymes is earthbound, maybe celebrated a little more than he is heard. His voice has lost its elasticity, and his demeanor is closer to youth basketball coach than living cartoon. He is an elder statesman of the genre, telling all the best stories on morning shows and interviews. Jay-Z has called him the greatest performer of all time; Phife Dawg calleds him “the James Brown of hip-hop.” He can still pick up the phone and get anyone to appear on his records, at any time, on the strength of his name: His independently released 2020 album E.L.E. 2: The Wrath of God featured Eminem, Kendrick Lamar, Rakim, Pete Rock, Mariah Carey, and Q-Tip—with Chris Rock acting as narrator.

Poignantly, the album also features some unreleased audio from the late Ol’ Dirty Bastard, chatting in the studio. “I wanna do more smooth rhymes and shit, man, know what I'm sayin’?” Dirty jokes. In the background, Busta gives a laugh of appreciation. An acknowledgment, maybe, of a fellow wild card in hip-hop, one who survived paying tribute to one who didn’t. When Disaster Strikes… was the turning point, the moment Busta Rhymes became the Joker of the deck that got to stay in the game.

0 comments:

Post a Comment