Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit the 1971 live double-LP from the Allman Brothers Band, a snapshot of a pure and joyous moment in rock’n’roll.

The Allman Brothers Band didn’t give a good goddamn about a photograph. It was early spring in 1971 in Macon, the comfortable little mid-Georgia city they’d recently adopted as their hometown because that’s where their upstart Southern label, Capricorn, lived. The sextet—two guitars, two drummers, bass, organ—had been a band for only two years. They’d passed most of that time on tour, playing 300 shows in 1970 and barely surviving on an unsteady diet of booze and blow, heroin and pot.

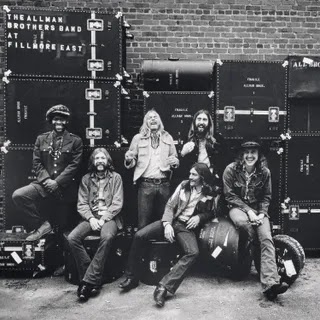

But after a spate of mid-Atlantic shows in April, they were home for just three days before another sprint through the even deeper South, including Alabama and Mississippi. There were kids, wives, and girlfriends to visit, a rare respite for a band that had suddenly exploded in popularity. And then, there was this stupid photo. Three weeks earlier, they’d played three (and recorded two) nights of marathon concerts at Manhattan’s Fillmore East, intending to compile the performances into an album that at last bottled the ecstasy and improvisation of their electrified blues-rock. The pictures they had taken in New York were a bust, so Jim Marshall—already a high-profile music photographer, having snapped Cash at Folsom and Coltrane and Miles in repose—had followed them home to Macon.

They should have been flattered, hosting this icon in their sleepy city. But they were tired, and much like the Grateful Dead, their pals and cross-country rivals as the best live band in the country, they never cared much for promotion, anyway. What’s more, Marshall was bossy. “A real son of a bitch,” drummer Butch Trucks remembered decades later, “who was lucky he didn’t get his ass kicked.” They scowled for Marshall’s first shots, a gaggle of roughnecks with matching mushroom tattoos, flexing their Southern roughness for the camera.

Just then, Duane Allman—the band’s founder, fixer, linchpin, and unparalleled guitar dynamo—spotted his local cocaine connection and sprinted down the alley. He returned to his spot, clutching an 8 ball in his hand and brandishing a Cheshire grin. The rest of the band howled, so Marshall took his picture and got his album cover, everyone locked in a laugh. He caught the band in their most natural setting: reveling in the joy and possibility of the present, the exact same way they sound on what is arguably rock music’s quintessential live album, At Fillmore East.

The Allman Brothers never intended to make their first live album, per se; they simply wanted to make their third overall album, and they recognized they were better onstage than in a controlled studio environment. Their self-titled 1969 debut, recorded five months after their first show, felt chastened, its straitlaced production and relatively short songs drawing the reins fast on a spirited young racehorse. Their second album, Idlewild South, worked to showcase a softer and more commercially viable side. Sure, it sounded good, but it also sounded dated upon arrival, a folk-rock reverie from a band that was best when it was wide-awake, very high, and very loud. “We get kind of frustrated doing the records,” Duane admitted at the start of the ’70s, noting that the stage was where they found their “natural fire.”

On the West Coast, the Grateful Dead had come of age—and shown their first flashes of greatness—by playing free shows in area parks, a tradition that early inchoate versions of the Allman Brothers pursued in their native Florida. (The Dead first met The Allman Brothers in an Atlanta park in 1969, the start of their enduring partnership.) And after three deeply uncomfortable studio albums, the Dead had also figured out they needed to record themselves live if they ever wanted wider audiences to understand how they actually sounded.

Early in 1969, the Dead opened a new frontier in rock production when their crew lugged a mammoth prototype of an Ampex 16-track tape machine up the stairs of San Francisco’s Avalon Ballroom. The technology afforded them the sort of control over recordings that would yield their first live albums and the early best-sellers of their career. The Allman Brothers again followed the Dead’s lead.

But the Allmans wanted to up the ante, too. The Dead’s live debut had been a patchwork from several shows in different rooms; they were not above adding studio overdubs, either, as they would soon do on 1971’s actually pretty decent Skull Fuck. For the Allmans, though, the ability to fix anything neared heresy—live, they reckoned, ought to mean live. They wanted no part of the running music-industry joke, guitarist Dickey Betts later said, that the only live part of most “live” albums was the cheering. They wanted to play in one room for several days, record themselves and the crowd, and create a snapshot of an actual moment that was both compelling and real. The Allman Brothers wanted to revel in—and preserve—the present.

And they knew exactly where they had to do it: Bill Graham’s Fillmore East, at 105 Second Avenue in the East Village. In San Francisco, the ambitious and inventive Graham had gone from managing a mime troupe to establishing a new paradigm for live music. At Fillmore West, he had ignored genre striation, pairing the Dead with Miles Davis and the Who with blues harpist James Cotton.

He recognized the same crossover zeal in five white hippies and a dauntless Black R&B percussionist from the South, who were setting new fire to old blues. Graham and his staff loved the Allmans the moment they opened for Blood, Sweat, & Tears in New York in 1969. Within weeks, they became a staple of both Fillmore East and Fillmore West, long before the rest of the music industry could figure out what to do with the band.

Their sets at Fillmore East offer a roadmap of their rapid progress. Opening for the Dead there in February 1970, they sounded fast and anxious, intimidated by the auspicious setting. But the Dead dosed the Allmans (and everyone else around) with Owsley Stanley’s acid, and something in the Southerners shifted. As Graham later put it, “the Allman Brothers were never the same again.” They were suddenly more aggressive, more open. By the Summer of 1971, when the band played their spectacular last-ever set at Fillmore East, Graham, not given to empty flattery, introduced them as “the finest contemporary music… the best of them all.”

The band shared that admiration, not only for Graham—“the fairest person,” Gregg Allman called him—but also for his New York room, a former Yiddish theater that became a hub for exploratory rock as soon as it opened in 1968. The productions were professional, the lights sharp, the crew familial and attentive, the sound crisp. “The acoustics were nearly perfect in there,” Gregg told Rolling Stone 45 years later. “I don’t think we even discussed another venue.”

They booked three nights, the first a mere warmup for the real “sessions”—four sets total, split over Friday and Saturday. Just as the Dead would do a year later in Europe, the Allmans parked a rented cargo truck equipped with a 16-channel machine in the rear, cables carrying the signal from the stage. The legendary Tom Dowd, a tech whiz who had recorded Idlewild South and Duane’s (superior) parts on Clapton’s Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, helmed the equipment.

Dowd had the band’s trust. He threw a fit, for instance, when an unrehearsed horn section appeared during the first night; by night two, they were gone. After each set, they’d grab booze and food and head to Atlantic Records to listen back and decide what to play next. There were no overdubs—only the moment, minus a few snips.

More than half a century later, the seven-track sequence that Dowd and the band culled from the 28 songs they recorded that weekend still feels like a revelation. Rock’n’roll has mutated into infinite shapes in the decades since, of course, but these pieces—sitting at thresholds of blues-rock and prog-rock, of pure soul and flashy technicality—still sound breathless, riveting, and wildly imaginative.

At Fillmore East is a condensed representation of an actual show, following much the same energetic arc as an early Allman Brothers set. (Remember, this is a band that had debuted less than two years earlier.) After Graham introduces them, they spring into “Statesboro Blues,” the Blind Willie McTell standard that inspired Duane to play slide guitar after he saw Taj Mahal and Jesse Ed Davis perform it in Los Angeles. Compact and charged, the song still gives the band space to showcase its dual guitar masters—Duane, whose slide leads sparkle with such melody that his younger brother’s singing feels like an afterthought, and Dickey Betts, whose comparatively understated playing restores the song’s sense of gravity.

“Done Somebody Wrong,” meanwhile, throbs like a crowded juke joint. The beautifully brooding “Stormy Monday” is a showcase for Gregg’s deepening techniques as a soul singer, his voice wafting above the band like a cigarette’s plume of smoke. This opening triptych is the Allman Brothers’ reference check, an offering of fundamental blues bona fides while nodding to the Black predecessors that made their music possible.

For a spell, “You Don’t Love Me,” an R&B hit for Willie Cobbs a decade earlier, feels that way, too, the band and harmonica pal Thom “The Ace” Doucette passing around the melody like a tightly wrapped joint. After everyone else falls away, Duane fiddles with the theme alone, trying to make a new shape from a familiar source. The band rejoins and follows his lead. Butch Trucks goes one way on his drums, while Jai “Jaimoe” Johanson goes another, as if Elvin Jones were trying to catch Charlie Watts at the other side of a maze. There are snippets of “Sitting on Top of the World,” a stunning bit of “Joy to the World,” and the prevailing sense that this band could do practically anything.

And then, well, it does: The second half of At Fillmore East is as vivid and exhilarating as recorded rock has ever been, especially at this relatively early but especially fertile point in its history. Anchored by Gregg’s stuttering organ and Berry Oakley’s lyrical bass, “Hot ’Lanta” feels like a game of instrumental hide-and-seek, each player seeing just what they can do with the theme before disappearing back into the safety of the band.

Written by Betts after an alleged tryst in the very Macon graveyard where half the band is now buried, “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” offers a keen testimonial to how much attention these Southern blues dudes were paying to emerging sounds and scenes far beyond rock. The textural interplay resembles Miles Davis’ then-new electric bands, organ and guitar oozing into one another like melting butter and chocolate.

The rhythm section ferries a righteous bit of funk, but the two-drummer setup allows Johanson and Trucks to work around the groove with a bebop sense of subtlety and softness. (Before joining the Allman Brothers, Johanson was on the cusp of moving to New York to play jazz, or “starve to death … playing what I love.”) Tilt your head one way, and “Elizabeth Reed” is a strutting, sexual rock instrumental; tilt it the other way, and it’s a deep improvisational hang, populated by players forever in search of some unimagined rhythmic intricacy.

No song makes it clearer that the Allman Brothers had never recorded a proper-for-them album than the finale, “Whipping Post.” Sure, they’d cut it as the farewell for their debut LP, when it was a dumb and fun five-minute rock song about being put out and misused by a woman you love—same old blues, different tune. Fifty years later, that version can still sit squarely between the Doors and Led Zeppelin in an afternoon FM rock block of songs by jilted androgenic bros.

But this 23-minute version is gloriously affirming, a diorama about being hurt badly and somehow persevering to work toward personal redemption. They first play the song straight through, Gregg screaming out his struggles at an elevated tempo that suggests he’s simply looking forward to hearing what comes next. The guitars soon take over, crisscrossing over the pounding rhythm section in a series of urgent solos, each a wrestling match with despair.

Duane and Betts quarrel until they collapse, the band going nearly silent while the guitarists sulk in a sort of cosmic instrumental grumble. But they pick each other up, rushing back headlong back into the song. When Gregg returns to the chorus after the long instrumental break, he sounds not like the victim but instead the victor, his struggles beaten back by the help of this ad hoc brotherhood. It is absolutely transcendent, based in the blues but rising above them.

The Allman Brothers finished playing the version of “Whipping Post” heard on At Fillmore East sometime around 5 a.m. It was the final set of their final night, and it had been delayed by a bomb threat that forced everyone from the building for hours. They rolled straight into “Mountain Jam” for 35 minutes, then responded to relentless calls for an encore with one more song.

“That’s all for tonight, thank you,” Duane said when it was over, despite the crowd’s cries for more. “Hey, it’s six o’clock, y’all. Look here: We recorded all this. It’s going to be our third album. You’re all on it.” (You can hear this proclamation on the 2014 edition, which includes every set.) Through his good-natured fatigue, you get some sense of what everyone in the room, crowd included, had accomplished—they’d made not only the Allman Brothers’ lone masterpiece, but they’d created and captured a crowning achievement of live rock’n’roll.

That moment and its glory would not last. Disenchanted with the music industry and financially saddled by sizable venues on separate coasts, Graham would close both Fillmore East and West by early July, 1971. Days later, the Allman Brothers released At Fillmore East, which would sell 500,000 copies in just three months, something their first two records did only when they were later repackaged as a pair. They beat their mentors and predecessors, the Dead, to that benchmark by three weeks—At Fillmore East, after all, was better than the overdub-laced Skull Fuck, preserving a moment of sheer power and finesse with perfect clarity.

But on October 29, four days after At Fillmore East was certified Gold, Duane Allman—home in Macon for another brief break from tour, leaving a birthday party sober—clipped a truck hauling a crane with his motorcycle, which landed on top of him. He died that evening from internal bleeding. He was 24. In the six months since taping At Fillmore East, the Allman Brothers had grown both sharper and more expansive, with Duane even talking about building a “big band.” It’s bittersweet, even shocking, to imagine just how far and hard he might have pushed their sound.

Under Gregg’s sudden leadership, the Allman Brothers Band returned to the stage less than a month after they played Duane’s funeral, convinced that’s what their visionary would have demanded. The extra material they’d recorded at Fillmore East became the backbone of their next album—the fabled resurrection of 1972’s half-live Eat a Peach. A few hiatuses excepted, they stayed on stage (even after the brilliant Oakley also died on a motorcycle a year later) until retiring in 2014.

The Allman Brothers Band were occasionally great during those subsequent 40 years, rotating some of Duane’s best electric disciples (including an extended family member, Derek Trucks) into the lineup. Still, they were forever after an aging band chasing the kind of joyous moment and youthful magic that At Fillmore East epitomizes. You can always find good spare parts, you know? It’s harder to find the guy who makes everyone grin in an uncomfortable situation by running down the street to score.

For all the perpetually obvious reasons, speaking about Southern pride feels fraught. Sure, many of our problems are not endemic to this place, but they are often brandished with particular relish or malice here, whether by Confederate flag or voting-rights restrictions. “Duane Allman was in the vanguard of the New South,” Rolling Stone’s Jon Landau once said. I think that applies to the whole band, which Duane liked to call his “enlightened rogues,” a pointed rejoinder to the stereotype of ignorant rebels. They weren’t perfect in this regard, of course—there are stars-and-bars (including a shirt designed for them by the extended family of the Dead) and questionable images in their closet, too. But by and large, the Allman Brothers provided an early model for young Southerners attempting to overcome their bigotry, bullshit, and fear to do something great, together. They still do.

When Duane returned to Florida with Johanson in 1969 to start the band in earnest, for instance, the pair moved into Trucks’ home. The white drummer was so scared of his new Black houseguest he assumed he was there to rob or kill him—at least until they started talking, at which point they became instant friends. By year’s end, they were one of rock’s great drumming tandems; by March 1971, they could swing, shuffle, and push harder than most anyone else in rock’n’roll.

What’s more, the Allman Brothers tacitly recognized the exploitative history of authorship here—from hush puppies on down to banjo music, whites have continually co-opted the work of their Black contemporaries. The Allmans accepted that they were borrowing from Black predecessors, from the songs themselves to Gregg’s soul mimesis, and they aggressively admitted it. They take so much care to acknowledge authorship during At Fillmore East that Duane corrects himself when he calls “Stormy Monday” a Bobby Bland tune. “Actually, it’s a T-Bone Walker song,” he says.

A white Southerner namechecking two Black musicians from stage doesn’t sound like a lot, but Bob Dylan still struggles to do half as much 50 years later. At least in that instant, the Allman Brothers were doing what they felt they could. And that ability—to make now better, however best you can—is the true animating spirit of At Fillmore East, from its beaming cover to its implicit politics. It is a tragedy that these seven songs captured one of the final moments the actual Allman Brothers Band would revel in together. But good god damn, at least we still get to relive it.

0 comments:

Post a Comment