Today on Pitchfork, we are celebrating the artistic bounty of Stevie Wonder with five new album reviews that span the breadth of his remarkable career.

Like the sidewalks of Hollywood Boulevard, Harlem’s Apollo Theater has its own “Walk of Fame” that displays the names of pioneering Black musicians. Stevie Wonder is one of them, his name carved into a plaque and embedded in the pavement in 2011, nearly 50 years after he first performed there. In 1961, then known as Little Stevie Wonder, he was one of the first child stars in the country to be signed to Motown. When he performed at the Apollo in December of 1962, it was clear that he was following in the footsteps of seasoned performers who had undertaken this necessary rite of passage.

By this time Wonder had already released two albums, A Tribute to Uncle Ray which was made up of Ray Charles compositions, and The Jazz Soul of Little Stevie, and toured across the country, entertaining segregated Black audiences as part of the “Motortown Revue.” Still, Wonder was so nervous during his Apollo debut that he dropped the bongos that he usually used to liven up the crowd in the middle of his performance. Wonder remembers Motown kingpin Berry Gordy chiding him for the fumble, but Wonder was unfazed. “Yeah, but I sang the song real good,” he replied back. It was a moment that proved that if he could keep the show going while on one of the most consequential stages in America, then maybe he could make a career from singing.

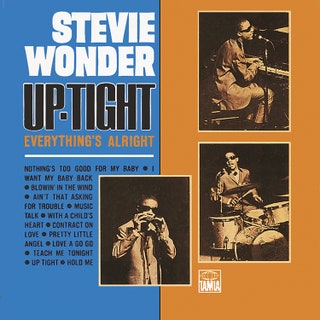

Four short years later, after dropping the “Little” from his name, Wonder released 1966’s Up-Tight.

At the time, Up-Tight was positioned as his last-chance album. There was fear among the executives at Motown that once Wonder’s voice matured in puberty, it would lose the crystal-clear clarity that had made him a phenom. It’s hard to fathom the idea that someone in their teens would find themselves fighting to stay relevant, but the music industry’s notoriety for wresting the life out of child stars to market their youth is unfortunately not new. Those who fail are left reeling with little money, and even less support, something Wonder would have observed in the rise and fall of Harlem-born singer Frankie Lymon, whose own transition from beloved child star to struggling adult performer highlighted the dark side of the business. Then just 15-years-old, Wonder had to make the album of his life, crafting recognizable hits and also the sound he hoped to create for the future.

The first track, “Love A Go Go,” is a swooping opener with a bounce and a step befitting a Hitsville release. The percussion and attention-seeking horns introduce the first notes and as the song continues it showcases Wonder as a master of space, able to envision how each instrument should perform as part of a group. There is a hint of hesitation in his vocals when he first comes in, almost as if he’s dipping his toes in uncertain waters, but by the second track, “Hold Me,” he’s confidently jamming aided by a pulsing percussion that builds and recedes at the right moments.

Popular session group The Andantes provide backing vocals on multiple album tracks, and on “I Want My Baby Back,” their harmonizing with Wonder is sublime. Co-written and produced by the dream team behind Motown’s assembly line of hits—Harvey Fuqua, Cornelius Grant, Norman Whitfield, and Eddie Kendricks—we hear Wonder’s notes almost crackling the vinyl, as if his collaborators just told him to let loose in the recording booth. Whitfield was one of the lead architects behind Motown’s distinct musical sensibility, writing songs for Marvin Gaye, Gladys Knight and the Pips, along with the Temptations of which Kendricks was the co-founder. By collaborating with Wonder, this duo helped ensure that the album was in the vein of prior hits that had emerged from the label. In the young musician, they recognized and honed a skill and ear for melody that made him singular. They knew how to craft a successful tune, and their involvement showcased Motown’s vested interest in making sure Wonder had all he needed to make an album that would sail across the charts.

The album feeds off the youthfulness of Wonder’s fans. The title track was a meeting of the minds between Wonder and singer-songwriter Sylvia Moy, a key Motown player who convinced Berry Gordy to trust in Wonder’s changing vocals and shifting artistry. The bouncy “Teach Me Tonight” and “Nothing’s Too Good for My Baby” were clearly produced to seamlessly fit a Dreamgirls type of choreography–fast-moving, outstretched arms, swaying hips and flirty glances. and yet for all its exuberance and lightness, there is an unmistakable and potent introspection that emerges on the cover of Bob Dylan’s “Blowin in the Wind.”

With his mentor Clarence Paul next to him, Wonder delivered his first work directly addressing race and inequality, producing a song that carries a heart almost too heavy for a teenager. The song had made Bob Dylan a revered songwriter in mainstream America, and in a tradition evident since the emergence of negro spirituals, Black artists took a known body of work and augmented it with insight and feeling that transmitted the brutality they witnessed and the hopes they carried. During his early days, on breezy tracks like “Hey Harmonica Man” and his rendition of “Dream,” Wonder subtly projected an existence that mimicked a swinging pendulum, constantly moving between episodes of grief and snatches of happiness.

As a young adult, he talked about the experience of creating in a country that for years placed him center stage then asked him to leave through the back-door. His political messaging was subversive enough to confound writers, including the Black journalist Jack Slater, who wrote for the New York Times in 1975 that “Stevie is largely spiritual youth in search of love and purity, while [Bob] Dylan is the bristling bull‐detector and, ironically, the restless, teeth‐gnashing, bad‐ass nigger.” It’s a jarring dissonance that side-stepped Wonder’s Blackness because it was seemingly absent of rage. This was nine years after the release of Up-Tight and after albums such as Where I’m Coming From and Innervisions where tracks like “Heaven Help Us All,” and “He’s Misstra Know-It-All” saw Wonder singing for freedom and holding President Nixon to account.

On the “Blowin in the Wind” cover, he holds listeners with both the cadence of a preacher, and the spirit of a young man finding a way to articulate the experience of being Black—using a celebrated invocation of oppression to make personal an unacknowledged harshness. From his teen years, the artist understood his position as a Black person in America, and moved softly enough that his transgressive art was misconstrued. Yet the music never faltered.

To take a step back and look at the album is to see a community in practice and motion. Wonder’s mentors and collaborators, decades older than the 15 year-old who they had known since he was 11, all brought their very best to make sure the homegrown boy had all he needed to come out on top. He was protected and supported, and it’s likely one of the main reasons he was able to stay focused on his commitment to music while tilling the ground that would birth his still unmade classics. Up-Tight is his album built by a tough-loving community, and Wonder is the artist he is because of those who made room for him to explore, experiment, and soar.

I have browsed most of your posts. This post is probably where I got the most useful information for my research. mobile

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete