Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit the Australian superstar’s 1997 departure to clubland, a misunderstood journey of self-discovery that became the black sheep of her catalog.

Kylie Minogue asks what if. In her radiant pop world, every feeling tingles with possibility: the longed-for romance that you barely dare whisper, the intoxication after just one drop, the liberation under the strobe light. She is love’s defiant crusader who, in her 1987 single “I Should Be So Lucky,” made being ignored by a crush sound flat-out delightful. She has an answer to everything; rejection is her gasoline. You don’t want my love? Put your hand on your heart and tell me. Most famously, she is consumed with an infatuation so dizzying it defies words, bubbling to the surface only as la la la.

The Australian artist’s music is an invitation to share what she feels, an ethos that has enthroned Minogue as an icon of positivity and a poet laureate of dancefloor communion. “It’s hard work being a Kylie,” said Björk, a friend of Minogue in the ’90s. “It’s a service to the nation. You have to smile and do handshakes—it’s like being a diplomat, or the Queen.”

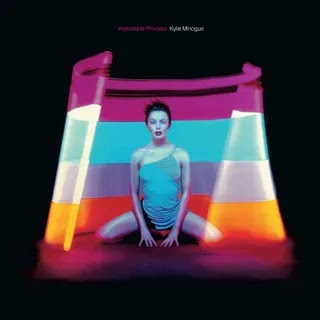

On her 1997 album Impossible Princess, pop royalty went rogue. Minogue simmers with rage, thrashing at the limits of torture and tenderness in a dark tango with the frenetic club music of the day. With help from a slate of buzzy producers, her unvarnished songwriting tangles with underground styles including pulverizing breakbeat and drum’n’bass, throbbing techno and ambient rave, as well as joyous jangle pop. If Minogue’s earlier music had been seen as a universal opiate, this was a mischievous abdication of civic duty.

Minogue considered the record a personal triumph. “I had people controlling me for years,” she told New Idea at the time. “Now I am reveling in the fact that I have control, I take responsibility for my decisions and I live and die by them.” But Impossible Princess was troubled by a messy rollout, label mismanagement, and some stale collaborations, making it more complicated than a straightforward artistic win. She would never make a record like it again.

Born in Melbourne, Kylie Minogue started acting professionally at age 8 in a period drama called The Sullivans. After a series of roles in her teens, she became a star in the UK and Australia thanks to a role on the sunny soap opera Neighbours, in which she played a tough-talking mechanic named Charlene. Within a year, Minogue became known simply as “Kylie” to an entire continent and was whooshing down the soap actress to pop star pipeline. She signed to PWL, the London-based label that was home to Stock Aitken Waterman (SAW), a British production trio that had helped to define ’80s Hi-NRG disco, crafting landmark singles for Dead or Alive, Divine, and Hazell Dean. SAW were the architects of Minogue’s sparkling early sound, powered by her winsome, youthful image and dance-pop that snapped like a rubber band. “They told me what to sing, what clothes to wear, and how to look in my photographs,” Minogue later said of PWL. She likened the experience to being “knee-deep in concrete.”

After four albums with PWL, Minogue signed to the independent dance label Deconstruction in 1993, favoring the small London imprint over offers from EMI and A&M for the creative freedom it offered. The promise turned out to be bluster. Her first release for the label, 1994’s Kylie Minogue, was meticulously A&R’d. That album boasts one of her best songs in the iridescent “Confide in Me” and some nice post-Erotica pop-house, but had plenty of missed opportunities too. A exhilarating Pet Shop Boys demo, “Falling,” was remixed into an elegant wisp (Minogue liked that decision; it sounded like Mr. Fingers, whom she adored). The label also nixed a Prince duet Minogue had been planning (Minogue did not like that decision). Deconstruction “had no idea what they wanted, apart from being different from the SAW stuff,” said Bob Stanley of Saint Etienne, who worked on two unreleased tracks for the record. Minogue later called it “a musical bridge over troubled waters”—one she had to “endure” to get to Impossible Princess.

Outside of music, Minogue’s three-year relationship with INXS’ Michael Hutchence had, she said, taken her “blinkers off” to a wider cultural world. She was a fan of dance labels like Mo’Wax and Source Lab, went clubbing at Aphex Twin’s legendary party Rephresh, and was listening to Tricky, Daft Punk, Massive Attack, and Beck. After what she described as a “Hollywood faux pas” in the 1994 turkey Street Fighter, she starred in a Sam Taylor-Wood art film, Misfit, lip-syncing to the last known recording of a castrato from 1904. In 1995, she duetted with Nick Cave on the murder ballad “Where the Wild Roses Grow,” singing from the perspective of a slain virgin. Performing the song on Top of the Pops with Cave, Minogue wore a dress from Alexander McQueen’s incendiary 1995 collection Highland Rape. She looked like a Pre-Raphaelite heroine ready to be reborn.

Minogue’s boyfriend at the time was Stéphane Sednaoui, a French-born artist and director who helped to define the scrappy, surreal aesthetic of post-grunge MTV with music videos like Smashing Pumpkins’ “Today,” Fiona Apple’s “Sleep to Dream,” and Alanis Morissette’s “Ironic.” To Minogue, Sednaoui represented freedom—and the kaleidoscopic escapes depicted in his music videos seemed like welcome relief from the paparazzi hounding her in London, where she had lived since 1990. The pair embarked on a series of trips to Australia, Japan, South Korea, and piled into a muscle car for a month-long road trip across the U.S. Minogue snapped photos on her Contax camera. She began writing in her notebook, and found that she had much to say.

Cave had passed Minogue a book by the British punk poet Billy Childish titled Poems to Break the Harts of Impossible Princesses, a collection which grapples with generational trauma and finding one’s place in a broken world. She brought the book along to an early meeting with Brothers in Rhythm, a British production outfit who had collaborated with Janet Jackson and Pet Shop Boys. Inspired by Childish’s writing, they began working on a song called “Dreams.” Here, too, Minogue asked what if? But for the first time, the target was her own desires, rather than canny twists on the pop playbook. “To taste every moment and try everything/To be hailed as a hero, branded a fool/Believe in the sacred and break every rule,” she sang, over lushly orchestrated trip-hop. “These are the dreams of an impossible princess.” Delivered with the sincerity of a fairy tale, Minogue’s earnest message of spiritual clarity is unexpectedly moving. On a 2022 episode of the This Is Disco podcast, Brothers in Rhythm’s Steve Anderson recalled his mindset after the session: “We have to scrap everything we’ve been doing [...] We have to create this blanket of safety to let her experiment, and we have to help her make the record that she wants to make.”

To record Impossible Princess, Minogue traveled with Brothers in Rhythm to Real World, a bucolic residential studio owned by Peter Gabriel. Over a weeks-long stay, the boundary between her life and creative process began to dissolve. She lived in a small house opposite the studio, working on demos in a glorified closet behind a maintenance room. “I was quite obsessed by my album,” she told Australia’s Feast Magazine. “It [was] like [an] ache that every now and then is really obvious. Which makes it sound like a bad thing, but it wasn’t.”

The resulting album is Minogue’s umwelt—her individual sensory world—made real, propelled by vibrant perceptions and impressions that are, at times, delivered with ferocity. “Too Far” is a phantasmagoria of frenetic drum ’n’ bass, breakbeat, sawing violins, buzzing bees, and layered pleas and screams. In the verses, Minogue can barely keep up with her thoughts, as if she’s frantically trying to capture the realization that every painful ending can be a wonderful new beginning. “‘Too Far’... is as psychotic as I’ve been,” she said in a 1997 interview with The Big Issue. It was the end of a relationship, and she was angry and hurt. “I went for a walk to the end of the street and into a cafe, and wrote it all down to get it off my chest. I got the moment by the throat by putting it all on paper.” Ten minutes later, the song was done. “Some of my favorite songs weren’t changed [after writing],” she said of the album. “No going back and rearranging. Just subconscious scrawl that formed itself, and I found those ones really pleasing.”

Minogue paired her raw automatic writing with vocals that shapeshifted to its moods. On the 140-BPM techno heater “Drunk,” she dances with oblivion, sounding wrecked over menacing strings. “Time and space and hurt and tears are not enough,” she slurs, bleeding into the next bar, before an accelerating beat brings an epiphany. On the industrial-dance whiplash of “Limbo,” co-produced by Soft Cell’s Dave Ball, she tries out jazzy impressionism over synths that rev and swerve. She shifts into unexpected registers—stretching some syllables, and cramming others into spaces where there’s only room for one: I’m HUUUUUURTing!/Helpmeout.

The album Minogue delivered to Deconstruction was quite different from the one we hear today. The label informed her there was no lead single, and cut fascinating experiments including the psychedelic trip-hop of “You’re the One,” the smoky jazz of “Stay This Way,” and a nine-minute interplanetary rave ballad titled “Take Me With You.” Minogue was paired with Manic Street Preachers, scuzzy glam rockers turned UK rock radio mainstays, in an attempt to get a hit. The trio rounded out the tracklist with “I Don’t Need Anyone” and “Some Kind of Bliss,” brightly gleaming Britpop moments that already felt dated by 1997, a year when even the subgenre’s architects like Blur were turning to alt-rock. The songs were an ill fit for the album, but, in a textbook bait and switch, “Some Kind of Bliss” was chosen as Impossible Princess’ lead single against the wishes of Minogue, who wanted “Limbo.” “Some Kind of Bliss” reached No. 22 on the UK charts, her lowest-charting single to date.

The British press called Minogue’s new musical direction “Indie Kylie,” a term which probably had more to do with the singer working with the Manics and her new cropped hairdo. But it cast a broader sense of suspicion over Minogue, as if she was masquerading for Cool Britannia points. In fact, Minogue’s music had never hewed so closely to the sounds dominating mainstream pop, particularly in the UK, where the charts are historically quicker to embrace the club. Nevertheless, the album was Minogue’s biggest commercial failure. Originally scheduled for September, it was hastily repackaged with the title Kylie Minogue following the death of Princess Diana in August—which made it, oddly, Minogue’s second consecutive self-titled album—and trickled into stores around the world that fall, before finally making its way to Australia in January 1998 and the UK in March. It stalled at No. 4 in Minogue’s home country and at No. 10 in the UK, but has since become a fan favorite: A 2022 vinyl reissue restored the album’s original title and charted higher in both countries.

Minogue’s effervescent voice was a perfect vehicle for PWL-era pop, but audiences and critics were unused to hearing darker themes delivered in a light lyric soprano—her register read as bubblegum. A Sydney Morning Herald review of Impossible Princess noted the lack of “guts in her voice,” and The Guardian said, of one track, that “it could be any breathy vamp singing it.” NME’s pan of Impossible Princess envisioned Minogue “singing into her hairbrush in front of her bedroom mirror, hamming up proceedings without anything approaching conviction.”

The world didn’t seem to know what to do with a cirrous voice singing about serious things. Minogue’s high-femme take on ennui had little similarity to Madonna’s late-’90s Earth Mother reincarnation, and even less in common with the grit and gristle of Grammy favorites like Alanis Morissette or Sheryl Crow. Minogue emphasized her comfort with higher registers on Impossible Princess’ most intimate songs like “Breathe,” an isolation chamber of airy subtlety, and “Say Hey,” a minimal techno trip cocooned in the purrs and sighs of self-pleasure. But the double standard ate at her. In 2020, she spoke of feeling like an imposter, asking rhetorically, “How are you being successful if they’re telling you that you can’t sing and your voice is not a valid voice?”

The notion of a pop star snatching the reins from label bigwigs to make a personal album is cliché. But Minogue’s late ’90s weren’t so much a matter of wresting control away from her bosses as working through their neglect. Deconstruction label head Pete Hadfield was unwell, and as a result the record company’s A&R department “hadn’t really been present for much of the album’s development,” wrote Minogue’s creative director William Baker in the 2002 book Kylie: La La La. “Creative control of the project was left with Kylie and Stéphane.” Minogue and Sednaoui were well-connected in the music world, but famous friends are no substitute for a seasoned A&R. A wider network of co-writers could have helped shape Minogue’s clunkier lyrics on songs like “Through the Years” and “Dreams”; additional producers might have opened the throttle on slight almost-anthems like “Cowboy Style” and the Japanese-edition bonus track “Tears.” The lack of support got to Minogue, who said in a 2000 interview with Rolling Stone Australia: “On some songs, lyrically it’s obvious to me now that I am saying, ‘I’m not waving. I am, in fact, drowning. Hello? Is there anybody there?’ At the time I felt like there was no one to help me.” A few months after the release of Impossible Princess, Deconstruction dropped her.

While Impossible Princess is Kylie Minogue at her most impish and spectacularly strange, it also offers insight into her private growing pains at a time when she felt abandoned by the music industry. Isolated and in a state of psychic turmoil, she threw off the burden of speaking for everyone and spoke only for herself. She is the girl who knows too much, who needs saving from herself. In its bracing honesty and crafty embrace of unexpected sounds, Impossible Princess shares a sibling bond with contemporaneous albums like Janet Jackson’s The Velvet Rope and Madonna’s Ray of Light, forming a trilogy of A-list experimental pop records in 1997-8 that addressed their artists’ fears, anxieties, and dreams. Minogue’s album is rather more scattered—fascinatingly so—but you can’t blame mainstream audiences for being reluctant to unpick a Gordian knot. Crucially, it has no euphoric floor-filler like “Together Again” or “Ray of Light,” moments of transcendence that drew pop fans to albums of wisdom and weight.

In her later music, Minogue avoided anything like Impossible Princess. She followed the record by signing to Parlophone and releasing 2000’s Light Years and 2001’s Fever, critical and commercial juggernauts that showcased Minogue at her dance-pop zenith. Understandably, she is no longer interested in creating music about her struggles. Not when civic duty beckons. In 2007, following a battle with cancer, Minogue released her tenth album, X, a collection of glossy electro-pop performed in structural outfits that resembled armor. Some wondered if she had considered bringing her private trauma into her music once again. “If I’d done an album of personal songs it’d be seen as Impossible Princess 2 and be equally critiqued,” she said. “I didn’t want every song to be about being ill. I wanted to do what I do.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment