Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today, we revisit Nick Cave’s early punk band and their pulpy, lurid, and legendary 1982 album.

To be a Birthday Party fan was and is to understand in one’s bones how much damage and electricity can be conducted through a truly spectacular new wave hairdo. “Thank you,” Nick Cave says at the end of the live version of Junkyard’s “The Dim Locator,” found on the raucous and essential Live 1981-82 compilation, “I love your haircut as well.” And hairdos, even metaphorically, the Birthday Party had in spades. The image of bassist Tracy Pew, practically shirtless and throbbing beneath an oversized cowboy hat, is as iconic a part of the Birthday Party’s mythos as the subway grate is to Marilyn Monroe’s. Whether it was Cave or guitarist Rowland S. Howard who popularized the long-sleeved shirt unbuttoned to the belly, that every frontman of every noise gothic cow-punk outfit has adopted since the early ’80s, the lineage of scrawny come-hither-ness that began in the Birthday Party’s camp is undeniable. They were the exemplar of having great hair as both aesthetic and ethos. There’s a reason that the Great Plains’ song “Letter to a Fanzine,” a 1987 nerd-punk anthem of scene-hierarchy jealousy, begins with the lines, “Isn’t my haircut really intense/Isn’t Nick Cave a genius in a sense?” In a sense, they all were.

By the time of Junkyard’s release in 1982, the Birthday Party (along with co-songwriter Anita Lane) had been in England for two years. Left behind in Australia was the band’s old name—the ironic and aptly teen-dreamy the Boys Next Door—and that old version of the band’s core influences: Roxy Music, the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, and more Roxy Music. “We became a bunch of sniveling little poofs,” bassist Tracy Pew said in a 1981 NME interview. Cave added, only slightly less problematically, “I used to wear frilly shirts and pigtails before any of this English shit. We committed the unpardonable error of playing to the thinkers rather than the drinkers.”

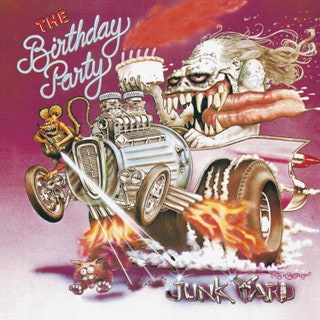

Complicating the shift is the fact that the Boys Next Door’s second album—1980’s The Birthday Party—was also the Birthday Party’s first album. While released under the original name, that album was written and recorded after the band heard the first convention-warping records made by the Pop Group and Pere Ubu, and were transformed. Though newly inspired, the Boys Next Door/Birthday Party album sounded like a near-complete transition into what Nick Cave, Tracy Pew, Rowland S. Howard, Mick Harvey, and Phill Calvert would become. With Howard’s mutant mosquito guitar and Cave’s yowl still changing from plaintively put-upon to predatory put-upon-er, the record utilizes the same jerking rhythms of the Fall, another band that inspired the decampment from Melbourne, but the Birthday Party’s sound is swampier, more soulful even, with horns and high-guitar squall giving a threatening silliness to the proceedings. It’s like the band was already driving the Ed Roth hot rod depicted on Junkyard’s cover, but drunkenly and underneath a circus tent.

Initially, the UK press embraced the Birthday Party with open arms. While plenty of post-punk bands like PIL and the Pop Group sounded like the ghosts of the free market, and there was already a few vampiric seducers like Bauhaus on the baritone scene, only the Australian transplants sounded like the wolfman, Frankenstein monster, and all the other underrepresented creatures of the collective unconscious. The mythmaking started early: That same 1981 profile in NME made an unintentional case for poptimism by using the avant-garde French dramatist Antonin Artaud as a point of reference and contrasting the Birthday Party’s violent realness against the “fools and phonies” music of Fleetwood Mac.

This high, dumb praise came just a few months after the release of the Birthday Party’s second long player, 1981’s Prayers on Fire, a near-perfect representation of the band’s delirious rhythm’n’skronk. Howard’s scabrous guitars slashed over Pew’s lurching yet lithe basslines. Both served as vehicles for Cave’s hiccups of desire and disdain. Whether the band’s bottom-fed frenzy was a more affecting ode to self-abnegation than the only slightly more subtle Fleetwood Mac is a judgment best left to the individual listener.

Less than a year later, another equally effusive NME review hinted at the English press’ shifting opinion of the band, saying, “the Birthday Party are awful. Subversively awful. Awesomely great. Awesomely brilliant.” Like many bands of the time, the young men played their own part in their complicated relationship with the press. They performed annoyed disinterest in interviews, bad-mouthed their peers, and seemed distinctly ambivalent about anyone liking them at all. “When we went back to Australia last year we were greeted with such acclaim and adulation it made what we were doing pointless,” Howard complained not long before the band’s breakup in 1983. “The whole life of the group had been based on reacting against what was around us and turning it into some kind of positive force. So once everything was positive towards us it defeated the purpose. We loathed it for the main part.” When the band was breaking up, Cave dismissed the Birthday Party as “trash” and “utter rubbish.”

The initial adulation is understandable. With the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to misremember the early ’80s as a sparkling parade of post-punk innovation and joy. But for every Joy Division or Slits, there were a hundred tuneless strivers who had the new boots and signed contracts but not much else. What the Birthday Party brought to the table was absent even among the actually good post-punk bands. If Echo and the Bunnymen and Teardrop Explodes (Cave hated these bands: “They were horrible,” he told NME in 1981) were digging through the ’60s for a psychedelic profundity and whole of punk looked to the ’50s for rock’n’roll “realness,” Nick Cave and co. looked at the same decades only for backwoods pulp and Hollywood detritus. They found Peggy Lee, Robert Mitchum chewing up the scenery, mafia-era Sinatra and his Rat Pack’s overblown love/hate relationship with the opposite sex, the Addams Family, and even the oeuvre of Mr. Sinatra’s daughter (the Boys Next Door covered “These Boots” and Rowland S. Howard and Lydia Lunch would, concurrent the release of Junkyard, do a version of “Some Velvet Morning”). Punk had perhaps correctly loathed the plasticine nature of showbiz, but the Birthday Party took the spectacle and blew it up, exposing and embracing the violence underneath. With, really, only the equally knowing Cramps and the utterly po-faced Misfits as peers, they approached pop culture like a comic strip sharing column space with the obits.

It didn’t hurt that the band managed to make a cohesively outré inversion of blues-rock that, while indebted to Captain Beefheart and the Stooges as everyone said, was equally within the traditions of absurdist, sophisticatedly wacky mid-century composers such as Carl Stalling, Raymond Scott, and Spike Jones. Sex and death abounded, but they were combined with lounge-funk vamps, eye-bulging awooga horns (and guitars played like horns), and a singer taking Mark E. Smith’s promise of a truly “hip priest” to its illogical conclusion. Cartoonish, yes, but a cartoon world where the holes Wile E. Coyote draws on the sides of mountains were both overtly Freudian and actual working tunnels that lead somewhere very dark and very hot.

Junkyard—its title, surprise surprise, a reference to heroin—was produced in part by Tony Cohen, who had produced the last Boys Next Door/first Birthday Party album, and Richard Mazda, who had worked on some early Fall tracks. On the surface, most of the songs on Junkyard are about killing girls, killing boys, killing someone of indeterminate gender, and getting into something disreputable while either driving or living in a trashcan in Texas. And doing a lot of heroin.

I won’t argue that the songs on Junkyard are not about the above topics. Without taking away from the smarts of its 5/4 time signature, the lyrics of “6" Gold Blade” (“I stuck a six-inch gold blade in the head of a girl”) don’t exactly lend themselves to a variety of interpretations. Nor am I insisting that the songs on Junkyard are necessarily about any specific thing. Howard’s “Dim Locator” (“Intriquintomitry treads on my trail/Entriggering traps for a gross gang of ghost types/Who later are packed in a cast iron trunk/These things have been known, to get out of their wraps”) is so enjoyably ludicrous that it’d be a shame to pester its mystery with presumptions of specific meaning.

But fun as it is to ponder how delightfully hairbrained gothic cowboy culture was before goth’s aesthetic shifted from “rhinestone cowboy junkie” to “steampunk Lestat in pleather,” the Birthday Party’s commitment to a theatrical bump’n’grind was not merely some internal fixation on homicide and hogwash. In the rich tradition of razzle-dazzle—whether freak show, creature feature, or Lennie killing all those lil’ mice and nice ladies—how the Birthday Party sang their song was arguably more important than the text of the song itself. They were, at the end of the day, putting on a show.

Throughout Nick Cave’s career, the most often referenced tentpole of his lyrics is his love of Southern gothic literature. He’s never been shy about drawing from the doom-pervert protagonist of Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood, or the polyamorous revelators of countless blues songs. Seeing The Johnny Cash Show on TV as a child, he’s said, gave young Cave his first indication that “rock’n’roll could be evil.” And certainly some of Cave’s ’80s and ’90s blues workouts (particularly with the Bad Seeds on Kicking Against the Pricks and The Firstborn Is Dead) are smothered and covered with enough Southern Gothic signifiers to make Jonah Hex blush. But, somewhere along the way, the application of “Southern gothic” to Cave’s concerns has become a trope unto itself. It discounts the gonzo noir of a song like Junkyard’s “Hamlet (Pow, Pow, Pow),” the Iggy-in-reverse come-on of “She’s Hit,” and even the influence of the cold, weirdo existentialism of another Cave favorite, Philip Larkin, in favor of reading all Cave’s lyrics as an ode to a murderous, hayseed-savant’s hand-scrawled bible.

The death drive of the Birthday Party has been well covered. Reasonably so, as that drive is apparent from the most casual perusal of the song titles, album art, or publicity photos. The band’s version of “kick out the jams, motherfucker” was, after all, Cave howling, at the start of their 1983 EP, The Bad Seed, “Hands up! Who wants to die!” But if the band was solely an exercise in violence and transgression, their appeal would mostly be contained to anhedonic edgelords, crime scene fetishists, men who dress like warlocks and bring their pet snakes to the bar, and other assorted transgression hobbyists. No, the Birthday Party’s flagrant sensuality must not be ignored.

Of all the bands that fit loosely under the umbrella of early-’80s “post-punk” bands, the Birthday Party was easily the sexiest. This is both obvious and the faintest of praise. As far as primal concerns went, being sexy wasn’t a big one for, say, Gang of Four. Only Bauhaus, fellow princelings in the “Don’t call us goth!” boyband olympics, came close. But Peter Murphy’s glam quartet was practically obsessed with being sexy, and even the most performatively minded sex-haver will tell you that too much effort can be a real turn-off. Couple Bauhaus’ preening with Peter Murphy’s somewhat ooky lifelong oedipal relationship with David Bowie, and the field for sallow-cheeked hip thrusters really opens up. Without discounting the Birthday Party’s reputation for being scary, their (anti-)religiosity, or the body count that came with all that intravenous drug use, what shines brightly about the music, in conjunction with its loony tunosity, is its sheer, feral horniness.

Junkyard, for its part, is a profoundly sexy record. It is sexy in Tracy Pew’s lumbering bass. It’s sexy in Phill Calvert’s stuttering snare. It’s sexy in Howard and Harvey’s transmogrification of Voivod-esque guitar stab back into the serpentine funk that birthed the sound. And, of course, Junkyard is sexy in Cave’s utilization of every trick in the James Brown/Don Van Vliet playbook to fully inhabit a drooling, yowling Elvis Presley-infected beast. Good sex can be a transcendent communion between two loving souls. Good sex can also be an unholy mess, a phantasmagoria of bodies and dark, ravenous need, akin to a sexy soccer team crashing into a sexy mountain range.

The Birthday Party, disaster reenactors onstage and off, performed the latter. Both Cave and Howard were in the throes of a substance dependency that would thread in and out of their lives for at least the next decade (Cave would eventually get straight after the sixth try at rehab; Howard would die at age 50). Harvey was generally dissatisfied with the band’s direction, or lack thereof. In ’82, Pew was arrested for drunk driving for the third time and served two and half months in a Victoria prison, necessitating Harvey and future Bad Seed Barry Adamson to play bass on “Kewpie Doll” and “Kiss Me Black,” respectively. And Calvert, while still drumming on the majority of Junkyard, was on the way out, soon to be slandered in interviews by his former friends as an all-around unimaginative musician. The men and women who made up the Birthday Party’s social milieu (the sick boys themselves, Anita Lane, Jim Thirlwell, Blixa, Lydia Lunch, Genevieve McGuckin) were of the age and disposition that mental health issues were both taken for granted and actively disregarded. Asked if Cave was depressed during this time, Lydia Lunch has said, “He was a heroin addict—of course he was fucking depressive.”

For Harvey’s part, in a 2012 Quietus interview, the multi-instrumentalist was agnostic on the topic of how much any internal or external hardships came into play, saying, “It’s impossible to appraise how much of the music was down to living in harsh circumstances and reaction to them.” That said, the overarching psychodrama of Birthday Party was probably part of what pushed the band’s previous tropes of rockabilly maximalism and Night of the Hunter rural noir even further on Junkyard. The producer Nick Launay, who recorded “Blast Off” and “Release the Bats”—two songs that were not on the initial album but were included on a reissued CD version—described to the Quietus how Harvey and Rowland tormented their singer by making him redo a particularly arduous verse over and over, less to get it right than to get off on his distress. On Junkyard’s sole moment of quietude, “Several Sins,” a pensive, boom-swagger-boom blues walk penned by Howard and his brother, the band gives Cave a breather. Though Cave would later express discomfort at singing any lyrics not his own, he doesn’t sound detached from the abstractly murderous apologia of “Several Sins.” He sounds like he’s sad, and exhausted by everything.

Or maybe not. The Birthday Party were of the post-punk school that eschewed straight confessionalism in their lyrics. Cave’s strength has always been the ability to convey lyrics as abstract as “Dim Locator,” as elliptical as “She’s Hit,” and as straight-ahead murder fantastical as “6" Gold Blade” as though he were telling the truest stories ever told from the pulpit, a Broadway stage, or the gallows. The stories may be too grotesque to take at face value. Threaded as they are to the rest of the band’s dramatic instincts, the stories also can’t be reduced to just abstract, elliptical, murder-fantastical ways of saying, “heroin, amirite?”

Even if punk made a big to-do about no gods, no masters, no heroes; even if the UK press briefly turned on the Birthday Party for not being as tasteful as the Jam’s Paul Weller; even if, after two decades, the American press wouldn’t truly embrace Nick Cave till enough terrible things happened to him that he dropped the hoodoo jive of “archetypes” and “metaphors” and gave critics the transcriptions of trauma which is the only art that many American critics understand; even with all that, the Birthday Party have become a myth. Not hugely, mind you, like Jesus or the Velvet Underground. But big enough that it’s hard to think of them without a pack of vampires showing up at one’s mental doorstep, clutching a hypodermic needle in one hand and the Collected Stories of William Faulkner in the other, scratching at the screen, begging for an invitation to enter.

This mythology was achieved partially because of goth-rock loving its own past as much as any subculture. It was achieved partially from the gravitational pull of Cave’s career. And it was achieved partially from the band’s own vision; the dragging of white blues into different territories of urban muck, the violent spectacle of their live shows, the music’s sheer insistence that it’s within the traditions of murder balladry, post-Stooges glam, and neo-deconstructed rockabilly. In a 1982 NME interview, Andrew Eldritch, the singer of Sisters of Mercy, said, “There was one great heavy metal group and that was the Stooges, and there’s only two bands around that can touch them and they’re Motörhead and the Birthday Party.”

The Birthday Party would, having kicked out Calvert, put out two more EPs as a four-piece. Both would be works of astounding beauty and both would be torn apart by the British press. By 1984, Cave would be, in a cosmic nod to early hyperbole, well on his way to becoming his own naughty version of Stevie Nicks, then Leonard Cohen, then Nick Cave again, and eventually he would take on his current role as Man with Some Important Things to Say. Mick Harvey would co-form the Bad Seeds and make a bunch of frankly delicious Serge Gainsbourg tribute records. Anita Lane would make a couple lovely solo albums but be misogynistically discounted as a muse. Pew would die of an epileptic seizure in 1985, Calvert would play the blues, and Rowland S. Howard would make a rich and devastating body of work with Lydia Lunch, These Immortal Souls, and finally solo, that few would pay attention to until after his death.

As of this writing, everyone involved’s hair is, in either this world or the next, still terrific.

0 comments:

Post a Comment